Ski the Last Degree: North Pole

2012 North Pole “Ski the Last Degree” Expedition

Introduction

In April of 2012 I took part in an expedition to the geographical North Pole. The trip was planned as a Ski the Last Degree Expedition but through an astonishing series of equipment failures, for three of the five of us, it turned into a trek over the sea ice.

…the sea ice in the vicinity of the North Pole is very much alive.

A journey to the North Pole is difficult but incredibly rewarding. Unlike the utterly lifeless frozen desert of the Antarctic plateau, the sea ice in the vicinity of the North Pole is very much alive. While lying in your tent at night you can hear the echoing booms of gigantic sheets of ice grinding against each other and the shrieks of others being wrenched apart by unseen forces of stupendous power. Every day while trying to make northward progress you are confronted by the chaos left in the wake of all this activity. It is one thing to read about pressure ridges and open leads of water but quite another to face them in person. The experience of confronting and overcoming these obstacles is unforgettable. The trip to the North Pole rewards the traveler with bone-chilling cold, long exhausting days of hard work, mental anguish and, upon finishing, the full measure of pride the comes from a job well done.

Beginnings

After completing a Ski the Last Degree expedition to the South Pole in 2010, it seemed natural to consider going to the North Pole as well. I loved absolutely everything about the South Pole experience and considered it a perfect apprenticeship for a trip to the opposite end of the world. Moreover, all of my companions on the South Pole expedition had already traveled to the North Pole and spoke highly about the experience.

We live in a remarkable age. With just a few clicks of a mouse, a couple of emails and a phone call anyone can sign up for a trip to the North Pole. The only qualification one must have is the ability to write a sizable check.

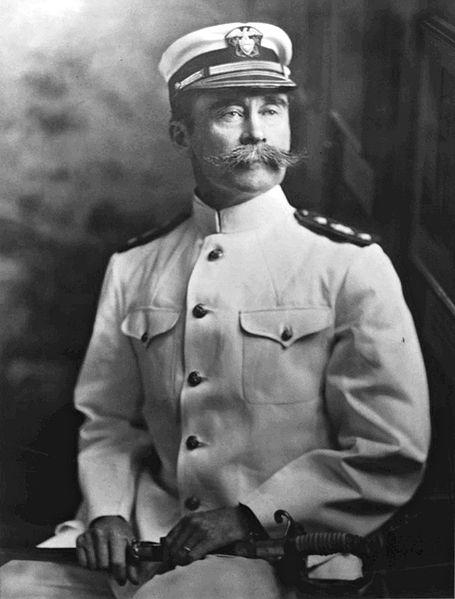

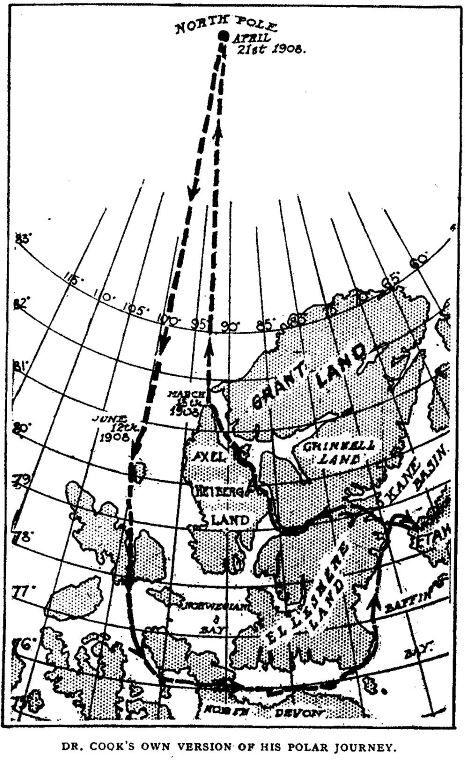

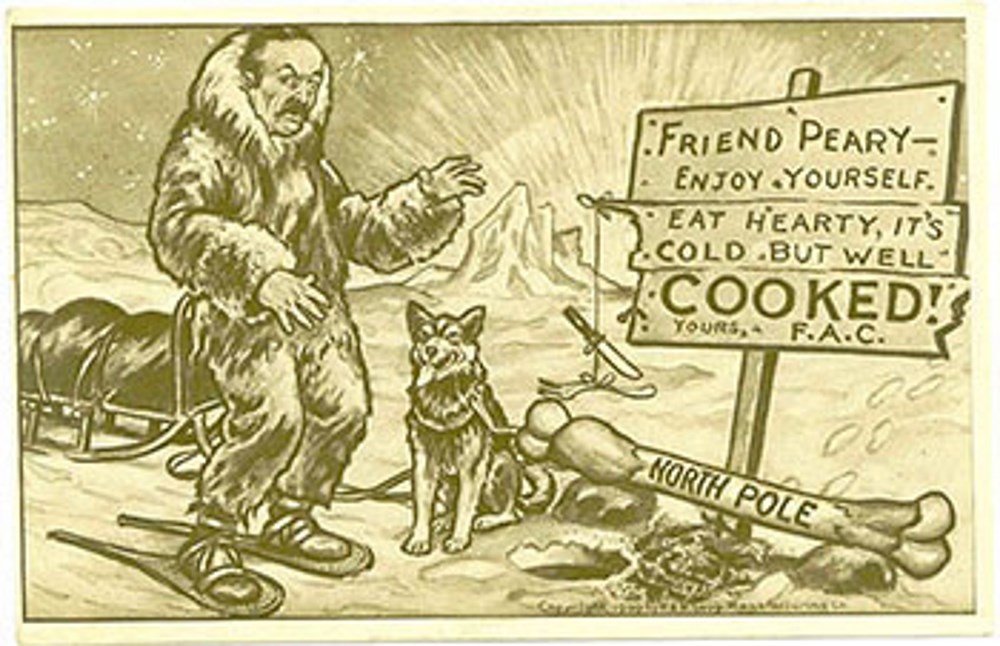

Things were a bit different a century ago when the modern pioneers of Arctic travel made their attempts to get there. While the American explorer Robert E. Peary is generally credited with being the first to arrive at the North Pole, his 1909 claim is dubious to say the least. Many historians doubt whether he came within fifty miles of the pole. Peary’s main competitor in the race to the pole, Dr. Frederick Cook, claimed to have arrived there in 1908. Cook’s claim might have been accepted too but for the fact that Peary’s public relations machine was able to convincingly establish that Cook had lied about having made the first ascent of Mt. McKinley some years before. Once branded a liar in the McKinley affair support for Cook’s self-proclaimed “attainment of the pole” evaporated.

…Who got to the North Pole first? The question is still shrouded in mystery.

So, who actually got there first? Probably a group of Russians who flew north in a World War II vintage aircraft and landed on the sea ice in 1948.

We are all so inured to air travel that it is difficult to imagine what the world was like before it existed. Moreover, even if you were able to mentally eliminate aircraft from the polar equation, it is even harder to imagine a world where the ships were of wood and their then state-of-the-art power plants were complex steam-driven units that, for all their size and fury, produced fewer horsepower than a modern Toyota Corolla. Icebreakers was we know them did not exist on the drawing boards of even the most futuristic marine architects.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, an assault on the North Pole required the organization and logistics of a military campaign. In current money, millions of dollars had to be committed to the enterprise and those voyaging north accepted that it would be at least two years before they returned home again. Those hardy souls swallowed hard and knew beyond a shadow of doubt that their time above the Arctic Circle would be dark, cold, cramped and miserable while they were aboard ship and much, much worse when they ventured onto the ice.

In the end, both Peary and Cook might have been shameless self-promoters. However, each had a capacity for suffering that only true zealots achieve. Peary, obsessed with the need for fame, made a remarkable seven expeditions north. In so doing he lost eight of his toes to frostbite and spent the best years of his life in lonely command amidst forbidding wastelands of ice. He regarded each and every one of his companions as a threat and potential usurper of the glory that was rightfully his alone. Unlike his contemporary, Antarctic explorer Robert Falcon Scott, Peary never seemed to find joy or inspiration in high-latitude places. For him, the quest for the pole was a battle and nature the enemy. There is no evidence Peary ever read Scott’s lyrical accounts of his Antarctic expeditions and of the brotherhood that exists among men united by a common purpose, but there is every reason to believe that he would have found them incomprehensible.

Peary was 53 years old when he claimed to have reached the pole. He spent twenty-three years of his life trying to get there and died just ten years later, broken in health and still uncomfortably mired in controversy about whether his discovery was legitimate.

Dr. Cook’s fate was worse than Peary’s. On the strength of a stellar record of success as a polar traveler in both the Arctic and Antarctic, his claim of priority was widely accepted despite the objections of Peary and his powerful supporters. The public was understandably skeptical of Peary’s demands that Cook present proof of his achievement for three reasons: 1) gentlemen do not lie, 2) Peary’s own “proof” of having reached the pole was little more than the account he wrote in his own diary, and 3) it was an established fact that Peary refused to allow aboard his ship the strongbox that contained Dr. Cook’s expedition diary and navigation tools.

It was a matter of unhappy misfortune that Peary came to be arbiter of the fate of Dr. Cook’s strongbox.

After a genuinely harrowing journey back from the pole (or wherever else it was that Cook actually went), Cook left the box in Greenland with a wealthy sportsman named Harry Whitney. Whitney had come to the Arctic the year before to do some big game hunting. He was stranded in Greenland awaiting a relief expedition to return him to New York. Both he and Cook were apprehensive that relief would not come and that they would be consigned to yet another winter in the Arctic. Because he was burning with desire to inform the world of his attainment of the pole (the news was by this time already more than a year old), Cook decided to travel light and fast to an area where his chances of evacuation were better. Whitney promised to safeguard the box and carry it home with him.

Cook caught the desired boat and was soon on his way to Denmark where his announcement created a worldwide sensation. Meanwhile, Peary had only recently returned to his ship from his own polar dash and was beginning to make his way back to New York. A port of call along the way was the place in Greenland where Whitney was marooned. Whitney promptly applied for passage.

…Peary has been described as “…undoubtedly the most driven, possibly the most successful, and probably the most unpleasant man in the annals of polar exploration.”

In what to this day must stand as one of the most brazenly churlish acts in the history of exploration, Peary decreed that Whitney would not be allowed passage unless he abandoned Cook’s effects. Whitney naturally succumbed to Peary’s demand and left the strongbox on the ice whereupon it was forever lost to history.

The public’s sense of fair play was offended by Peary’s conduct and was further outraged when his advocates used Cook’s “lack of proof” of having attained the pole as the lynchpin for rejecting Cook’s claim. Having personally engineered the loss of Cook’s “proof”, the public was openly hostile to Peary’s demand that it be produced. Still, Peary had powerful advocates and money and organization that dwarfed Cook’s. The battle for public opinion dragged on for years until Peary’s propaganda machine stumbled on the smoking gun that wrecked Cook’s credibility and brought him to his knees.

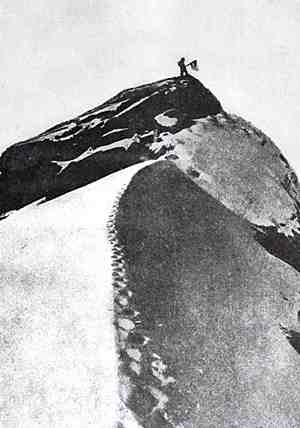

In 1906 Cook claimed to have climbed Mt. McKinley, the highest mountain in North America. In fact, he never did such a thing.

There were three problems with the claim, none of which were recognized until Peary’s sleuths uncovered them. (Remember, at the time it was accepted that gentlemen do not lie.)

First, the “summit photograph” that Cook used to support his ascent was clumsily cropped and included a sliver of another mountain in the background. Careful study allowed the other mountain to be identified and triangulation from it led inescapably to the conclusion that the picture was taken miles away from the McKinley massif.

Second, Cook’s expedition log contained a description of his route to the summit. Other mountaineers travelled to Alaska to recreate the route and promptly found that it simply does not exist.

Third, under pressure from Peary’s detectives and lubricated with a hefty bribe, Cook’s climbing partner told all and confessed that the ascent was a lie.

Cook proffered a passionate rebuttal but it was all for naught. He suffered what appeared to be a nervous breakdown and for years became a furtive, impoverished outcast living on the fringes of society. He resurfaced in the 1920s as an oil lease promoter whereupon he was accused of fraud by disappointed investors. He spent years in federal prison for this offense and it was slim consolation when the oilfields in question later proved to be prolific far beyond what he had claimed. He was pardoned by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1940, shortly before his death.

Whether fairly or unfairly Peary won the fame he so desperately desired. However, the official recognition of his life’s work contained an important asterisk that surely must have haunted him to his dying day. The 1911 Congressional “Thanks of the Nation” that he received lauded him as the “attainer” of the pole rather that its “discoverer.” This nod to the possibility of Cook’s priority was a rebuff so subtle that most never noticed it. There is no doubt that Peary noticed and took it very hard indeed.

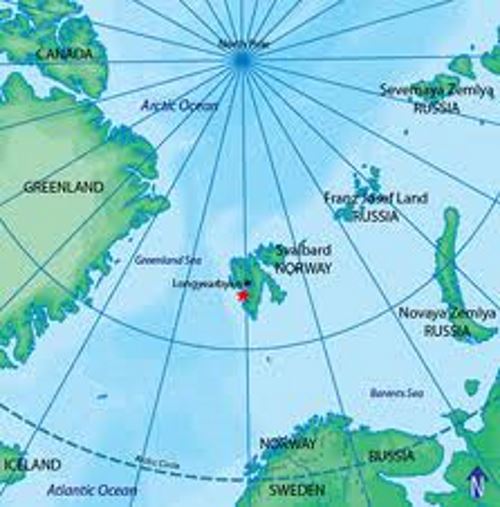

So, we modern travelers have it easy. We can fly from any part of the world to Svalbard, check into a comfortable hotel and the next morning board a charter flight that will land on the sea ice in the vicinity of the North Pole two and a half hours later. From there we can hop on a helicopter that will take us to 90º North with an accuracy that the early explorers could scarcely imagine. The whole round trip to the pole from Svalbard can, if the traveler so desires, be accomplished between breakfast and dinnertime at the hotel.

For many travelers a one-day round trip to the pole is the answer to a lifetime dream. By any way of measuring things it is adventure of unique distinction. In the history of the world fewer than two thousand people have walked on the North Pole. The likelihood of meeting another polar traveler at a cocktail party is less than that of meeting an Olympic gold medal winner.

However, as exciting as a tag-the-pole trip is, for many folks, the adventure would not be complete without a dash of suffering. For them, a Last Degree Expedition fits the bill perfectly.

…In a Last Degree Expedition, the object is to make your way from 89º North to 90º North, a straight-line distance of sixty nautical miles.

In a Last Degree Expedition, the object is to make your way from 89º North to 90º North, a straight-line distance of sixty nautical miles. Sixty nautical miles is equivalent to sixty-nine statute miles and one hundred eleven kilometers. The trip is typically done on ski and takes eight days to complete. During those days on the ice the traveler gets to experience firsthand what it takes to haul a heavy sledge for hours on end, what it is like to be confronted with gigantic pressure ridges and how it feels to be chilled to the marrow by a cruel sub-zero wind.

To a man, virtually all Last Degree expeditioners have read the accounts of Cook, Peary, Fridtjof Nansen and the other polar pioneers. They are conversant with the ironic fact that Roald Amundsen, a man uniquely qualified to be the conqueror of the North Pole, was dissuaded from going there because he believed that Cook and Peary had beaten him. Undaunted, Amundsen switched objectives and focused his attention on the South Pole. His 1911 trip to that end of the Earth was executed with textbook precision and, learning from the Peary / Cook contretemps that someone might actually demand proof of the achievement, Amundsen brought home incontrovertible evidence of having been to Antarctica’s geographical axis.

Sixty nautical miles is a small thing when compared with the nine hundred or so that Peary and Cook had to confront. However, in doing the Last Degree to the North Pole history comes alive in a way that is incredibly powerful. The sea ice in the region of the pole has not changed materially in hundreds of years. The challenges to northward progress that today’s sledger faces are identical to the ones that confronted the early twentieth century travelers. It is one thing to read in a book about “terrific pressure ridges” and hours spent searching for a way across open leads of water. It is quite another to meet these obstacles in person and take their measure. This kind of education is hard-won and all the more valuable for that.

What follows is my diary from a Last Degree Expedition that I did in April of 2012. I have never had a stranger April but I am sure never a better one.

Friday and Saturday, March 30-31

There are no direct flights to Svalbard from the United States or most anywhere else. My itinerary from Houston included plane changes in Frankfurt, Oslo and Tromso. From start to finish in Longyearbyen, the main city in the Svalbard archipelago, the trip took twenty-six weary hours.

All Last Degree Expeditions and polar day trips require a visit to Svalbard. The reason is that it is the sole embarkation point for the Antonov aircraft that brings adventurers to Barneo Ice Station, the Russian Geographic Society’s seasonal base near the North Pole. Barneo is built from scratch every year in late March and rarely lasts beyond the end of April. Its location varies from year to year depending on ice conditions but the goal of its builders is to establish it on a big piece of stable ice as near to the pole as possible. Once the location is chosen, helicopters ferry men and equipment to the site and an ice runway is prepared to accept the Antonov aircraft. When the runway is completed, the Antonov then shuttles back and forth from Svalbard to bring the bulk of the equipment needed to outfit the base.

I was thrilled to come to Svalbard. Longyearbyen, which is located on Spitsbergen, the largest island in the archipelago, is at 78º North, making it the most populous high-latitude place on Earth. About two thousand people live in or around Longyearbyen. They are outnumbered by polar bears by two-to-one.

On arriving at Longyearbyen’s modern and efficient airport I was happy to see a representative of Agency Vicaar Ltd. there waiting to provide a welcome and transportation into town. I had chosen St. Petersburg, Russia-based Vicaar as the outfitter/guide for my Last Degree Expedition for three reasons: 1) they had a long track record of success, 2) their price was competitive and 3) their head man was Dr. Victor Boyarsky, a famous polar traveler who, in the late 1980s was a member of a small team that made the longest polar journey of all time, an epic seven month, 3,700-mile dogsled crossing of Antarctica from the tip of the Antarctic peninsula to Mirnyy Base clear on the other side. Also, since I knew that Barneo was run by the Russians it seemed reasonable to assume that Vicaar would have a communications edge with the Barneo team that we would be relying on once the expedition got underway.

On the drive to the hotel, Leo, the Vicaar representative, updated me on the status of my trip. He said that conditions near the North Pole were terrible, minus 40ºF and stormy. The weather had delayed construction activities at Barneo and a delay in flying there was almost certain. My flight to Barneo was scheduled for just four days later (Wednesday, April 4) and Leo said that there was little chance that it would go as planned. On a more positive note, he said that another person had been added to my expedition team. I had previously heard that two Russian clients had signed on and now we would have an Italian one as well. He said that the guide was a Czech so ours would definitely be an international expedition.

…in polar regions delays are the rule rather than the exception.

I took the news of a delay in stride. I had learned from my trip to Antarctica that in polar regions delays are the rule rather than the exception. I was ready to wait out the weather however long it took. This feeling of peaceful resignation was bolstered by the fact that my hotel, the Radisson Blu-Polar Hotel, was very comfortable. Check-in was quick and efficient and the wireless internet connection is as good as the one I have at home. By 9 pm I had fired-up my laptop and downloaded the last couple of day’s email. It was very pleasant to have all the electronic conveniences of home here in faraway Longyearbyen!

Sunday, April 1

It was fun to wake up in Longyearbyen and look forward to a free day to poke around and get a flavor for the town.

The hotel offered an outstanding buffet breakfast that is included with the price of the room and I took full advantage of it. I will definitely not starve while staying here.

After breakfast I went outside and used my GPS to log the hotel’s distance from the North Pole. It is just 817 miles from the front door. This proximity means two things: 1) it is cold pretty much all the time (10ºF, today) and 2) it never gets dark at night this time of year. Last night it darkened to twilight conditions but never more than that. Quite sensibly, the rooms in the hotel have blackout curtains that allow you to simulate full darkness.

The town of Longyearbyen is a bustling place. It sits in a valley with snow-covered mountains rising above it on three sides and terminates at the sea. A natural bay protected by tall, snowy mountains on the opposite side is big enough to welcome large ships.

In the town proper there is a very nice pedestrian walkway with shops, restaurants and services. Arrayed on the low hillsides above the mall are cozy-looking row houses where most of the full time residents live. Everything is neat, sensibly sized and prosperous-looking. I browsed through a couple of extremely well equipped sports shops and found that you could buy anything your heart desired for arctic conditions right there. Of course, the sky-high prices made me very grateful that I had arrived with my full kit and did not need to do any last minute shopping.

The most interesting feature of the town is the tramway towers. There are tram towers everywhere you look and they proceed for miles in every direction. They march through the center of town to the port and up, down and across the mountains. They are big wooden affairs and though no longer operational they give cogent testimony to the economic power that the coal mining industry had in Svalbard in years gone by.

After being discovered in 1596 by the Dutchman, Willem Barents, Svalbard remained very lightly populated until the beginning of the twentieth century. It was then that an American named John Munroe Longyear appeared on the scene and opened the first commercially successful coal mine. The archipelago’s coal resources proved abundant and transformed it from a frozen backwater to a place where hundreds of miners and their families could make a decent living. The tramways were constructed to transport the coal from the mines to the port. They were like giant ski lifts for coal. Big buckets were filled with coal at the mine face and sent to town via the trams.

While coal mining has slipped to second place (after tourism) in economic importance, Svalbard’s mines are still producing to this day. Supplanted by roads and motor transport the tram towers are being preserved as a part of Svalbard’s cultural heritage.

Before coming here I had heard that the archipelago boasts the largest concentration of polar bears anywhere in the world and visitors had to be wary lest they meet one on the street. Based on the amount of activity in town it was clear that the central area was perfectly safe. However, it was equally apparent that the threat was taken seriously by all residents. Snowmobiles are the favored means of transportation on Svalbard and a great many of them had rifle cases mounted within the driver’s easy reach. In addition, virtually all of the cross-country skiers I saw were shouldering rifles or wearing pistol holsters. At the hotel, stories circulated about how “just last week” some incautious camper was done in by a marauding bear.

After my walkabout I bumped into Leo in front of the hotel and he introduced me to Victor Boyarsky, Vicaar’s head guy. Since Victor is a genuine polar legend I was thrilled to meet him. I told him that I had read all about him. He laughed and commented, “Not everything you read is true!” He confirmed that the Barneo construction team was struggling with bad weather and said that there would be an update in the evening. On the good side, he said that the guide for my group, Miroslav Jakeš, had just arrived in town and that the other members of the team were arriving tomorrow.

At 6:30pm I went down to the lobby for the update. Leo offered that my group would be the first Last Degree group of the season but was unable to predict how long a delay we were facing.

My guide, Miroslav, was with Leo and we had a good opportunity to talk. Miroslav is 61 years old (!!!) and has been to the North Pole thirteen times. He has climbed five of the Seven Summits (Mount Everest and the Vinson Massif are too expensive), done a solo unsupported crossing of Greenland and an incredibly rare winter ascent of Aconcagua. He lost most of his toes on the Aconcagua climb. His website contains a good chronicle of his achievements.

According to Leo, Miroslav is the most experienced polar guide in the world. His first trip to the pole was in 1991.

Miroslav seems like a good fellow and his resume is absolutely exceptional. My only reservation is that his English skills are marginal at best. His English is approximately as good as my Spanish. This is not an ideal situation in circumstances where failures in communication can have dire consequences.

Monday, April 2

As per last night’s plan, Miroslav stopped by my room at 10 am to do a gear check. My stuff was all in good order and the only open question was whether I should use my minus 100ºF-rated Baffin boots or a lighter but more comfortable pair of minus 40ºF-rated Sorels. Not surprisingly, Miroslav favored the Baffins.

…the team assembles in Svalbard. Everyone is admirably fit and experienced.

After the gear check we went to the hotel lobby and met with the two Russian team members. Alexander (“Sasha”) is a 55 year old surgeon from Moscow. He is tall and big all around. He looks very strong. Roman is another Muscovite and 40 years old. He looks very fit. He successfully summited Mount Everest from the Tibet side last year. Both guys speak passable English. Their communication with Miroslav was effortless. It turns out that Miroslav is completely fluent in Russian. The logic of Vicaar’s choice of him as guide for our group was immediately apparent.

Following introductions, Victor Boyarsky also turned up in the lobby. He said that it looked like our fight north would be delayed only one day, leaving on Thursday, April 5 rather than Wednesday as per the original schedule. Welcome news!

Miroslav led us to the “hangar”, a big warehouse a short walk from the hotel where Vicaar and several other guide companies store their gear. There we were given sledges and drew tents, skis stoves, shovels, food packages and other equipment for the trip.

We practiced erecting the tents and lighting the stoves in the snow outside the hangar. Much to my dismay, the tents are fussy five-pole mountaineering tents that take quite a lot of effort to put up. Also, the stoves are huge two-burner Coleman units that look more suited to a Boy Scout Jamboree than a trip to the end of the Earth. However, these disappointments quickly faded when Miroslav announced that he and I would be tenting together on the ice. With Miroslav as my tent-mate, I’ll be able to rely on him to help get the tent up and do most of the cooking. The plan is for the Italian guy to tent with the Russians.

We also got to try out the Vicaar-supplied skis and I was not entirely satisfied with them. They are a bit wider than traditional cross country skis but much narrower than the backcountry skis that I like best. With my ultra-wide feet backcountry skis are ideal. I asked Miroslav to see if he could find a pair of these for me to use. He said he would talk with Victor.

It was chilly outside as we ran through our tent building, stove lighting and ski practice drills and by the time we were done I was very happy to get back to the nice warm hotel. With all the talk of storms and minus 40ºF up north it is easy to lose sight of the fact that 13ºF is mighty cold for just about anybody.

During the afternoon Miroslav announced that Vicaar would be hosting a dinner for our group later that evening. I looked forward to the dinner as a good opportunity to get to know Sasha and Roman better and finally meet our Italian team mate.

The dinner was held at Mary Ann’s Restaurant, just a stone’s throw away from the hangar. It had a rustic, woody décor and lots of skis, snowshoes and animal hides on the walls. Somewhat incongruously it featured Thai food.

While we were enjoying a before-dinner drink Leo came in and said that he had just picked the Italian guy up at the airport and that he would be joining us shortly. However, there was just one small change: it turns out that the Italian is really a black South African. His name is Sibu. How the communication lines got so fouled up is a puzzle to everyone.

Sure enough, Sibu arrived a few minutes later and our team was finally complete.

If I was impressed by Miroslav’s resume, I was utterly blown away by Sibu’s. Now 41 years old, he is the first black African to have summited Mount Everest and also first to have completed the Seven Summits. He has a 65-day unsupported all-the-way trip to the South Pole to his credit, another first. His initial climb to the summit of Everest was done via the South Col route. His second (!) was done on the north side of the mountain. If he is successful on our Last Degree Expedition he will be among the tiny handful of humans to have completed the Three Poles Challenge (Everest, South Pole, North Pole). Needless to say, this will also be a first for a South African.

His accomplishments have earned him personal audiences with both Nelson Mandela and the Queen of England. A South African subsidiary of Sir Richard Branson’s Virgin Group is sponsoring his trip. And, as important as anything else, Sibu is a thoroughly nice person with a genuine modesty about him. His website is excellent and well worth a look.

The dinner was a rollicking affair and everyone had a good time. I wish I knew Russian because Sasha, Roman, Leo and Miroslav were in stitches half the night. We all exchanged personal details about family, kids, jobs, etc. and in the course of the evening made good progress towards molding the group into an effective team.

Tuesday, April 3

During dinner last night Leo announced that it looked like our departure for Barneo would be delayed a further day until Friday, April 6. In order to take advantage of the extra day it was proposed that we do an overnight camping trip, skiing a few miles up the glacier south of Longyearbyen.

We gathered in the hangar in the morning and I had a chance to see whether Miroslav had made any progress towards securing a pair of backcountry skis for my use. What he offered was the same old skis with slightly wider skins; no help.

Also in the change department, Miroslav decided to make our outing a day trip rather than an overnight. This met with universal approval. We will have plenty of opportunity for doing overnight camping by and by.

We set off on our adventure in midmorning. Conditions were absolutely beautiful with the temperature in the single digits and bright, sunny skies. Since we travelled up the glacier on a route often used by snowmobiles, the snow was firmly packed and conditions close to ideal. After a couple of hours we were about five hundred feet above the sea and two miles south of the town center. The view down the valley was spectacular. We stopped at this point, unloaded the sledges and built camp. Based on the fact that we are both English speakers, Sibu and I will be tenting together. Sasha and Roman will share a tent and Miroslav will go solo in his own tent.

I immediately wished I had paid more attention when the mysteries of the tent and stove were explained the other day. However, before too long Sibu and I had both sorted out and were relaxing over a fresh pot of tea.

After lounging around for ninety minutes or so, Miroslav roused us for a ski further up the glacier. This was great fun because we gained another thousand feet of altitude and left the sledges in camp. Unfortunately, Sibu had a lot of trouble with his skis and wound up doing the distance on foot.

Proving that even elite athletes are not immune from equipment problems and organizational snafus, Sibu related the checkered history of his trip while we were in the tent.

He had signed up for a Last Degree Expedition with an organizer other than Vicaar. He had been promised a two-man expedition with an expert Norwegian skier as guide. He paid for the trip on that basis. However, the trip organizer never delivered on the promise and in the eleventh hour asked Vicaar to take Sibu on. Knowing that Sibu wanted to use the same kind of 75mm (Nordic Norm) skis and boots that he had used on his South Pole trip and that Vicaar did not have these, the organizer assured him that it would supply them. Amazingly, the skis that were delivered to Sibu in Longyearbyen were sorely deficient. The problem was that they had half skins rather than full ones. Without the traction provided by full skins, going up even a modest grade while pulling a sledge proved impossible. Sibu polled a few experienced polar travelers to gain an opinion on whether his skis would be adequate for North Polar conditions. The best answer he got was “maybe” but on the basis that the boots and skis went together and the only alternative was a prohibitively expensive shopping expedition in Longyearbyen, he was stuck with the equipment for the duration. So, even professional athletes are sometimes disappointed!

The descent back to town was uneventful and I arrived back at the hotel by 7pm. However, like Sibu, I am not entirely satisfied with my skis. They were adequate in the perfect skiing conditions we had on the glacier but I had no illusions that the sea ice would be so ideal. My plan is to see if I can rent a pair from another guide company or from one of the sports shops in town. Since tomorrow is a free day I should have plenty of time to sort things out.

Wednesday, April 4

Big changes are in the offing.

Sasha stopped by at noon to tell me that he had seen Miroslav and that we would be flying north to Barneo base tomorrow instead of Friday.

I hustled over to the hangar with the remainder of my gear and packed my sledge. I decided to take everything but the kitchen sink with me, extra clothes, both jackets, the Baffin boots as a backup in case the Sorels proved too cold, camera, GPS, etc. While all of this made my sledge impressively heavy I thought that it made better sense to be over-equipped than to risk lacking something. It is a long way to the nearest store when you are on the sea ice.

…Proving that good luck and timing are everything, while at the hangar I bumped into a guide for another company who I knew from a climb in the Himilayas ten years before.

Proving that good luck and timing are everything, while at the hangar I bumped into a guide for another company who I knew from a climb in the Himilayas ten years before. After marveling at the fortuity of meeting on Svalbard (small world!) after all those years and reminiscing about our Cho Oyu climb, I asked my friend whether he knew of anyplace where I could get a pair of backcountry skis. His response was immediate, “Sure, use a pair of mine.” With that he led me to his company’s area in the hangar and pulled out a brand new pair of skis that were exactly what I had wished for. Problem solved!

I tried out the new skis and they are perfect. It is hard to describe what a boost it was to me to get the new skis. I was dreading having to cope with the old ones. Now my confidence is fully restored and I am looking forward to getting onto the sea ice without any reservations.

According to Miroslav, the flight north will be at 2 pm tomorrow.

Thursday, April 5

This has been an incredibly eventful day.

After a series of delays we were finally picked up at the hotel and brought to the airport at 3 pm. An hour later we were loaded onto the Antonov and flying to the pole.

The Antonov AN-74 aircraft is a highly specialized thing capable of carrying a prodigious load of passengers and gear. On our flight I counted thirty-six passengers, thirteen of whom (including us) were Last Degree Expeditioners. The remaining people were day-trippers, a large film crew and Barneo staffers.

Despite being jammed to capacity, the Antonov popped into the air effortlessly before we were halfway down the runway. It is a STOL (Short Takeoff and Landing) aircraft and the exhaust from its jet engines is actually ducted over the wings to contribute to lift. Clever!

The flight north was smooth and comfortable. Unfortunately, the Antonov only has windows for the first three rows of seats and I was unable to sight-see along the way. The flight took about two and a half hours and at 6:30 pm we tumbled out onto the ice at the alien world that is Barneo.

…upon arriving at Barneo the only thing that you actually notice is that it is overwhelmingly, breathtakingly cold.

It is easy to describe what deplaning at Barneo is like. You see the ice runway that the Antonov landed on and a huddle of blue and gray Quonset huts close by. You see staff rushing about to unload the plane and prepare it for an immediate return to Svalbard. However, the only thing that you actually notice is that it is overwhelmingly, breathtakingly cold. The cold catches you unawares because it is so much more extreme than anything your experience has taught you to cope with. It is interesting that even after months of preparation and planning to be at this very spot, the brutal reality of the cold comes as a gigantic shock.

After assisting with the unloading of the plane and moving our sledges to the staging area we were hustled into one of the huts. Before getting inside we had to dig through our sledges to retrieve goggles, ski poles and other items that had to be on the ready for the trip to 89ºN. I instantly found out that it was unwise to do this with bare hands despite the awkwardness of dealing with buckles and straps with gloves on.

Once inside the hut, the atmosphere was friendly and warm. A big canister of hot water for tea or instant coffee was bubbling away and plates of cookies and candy bars were distributed throughout the place. While we were enjoying all of this, Barneo staff gathered the Last Degree guides together for a meeting, the substance of which was that conditions on the ice were very challenging.

Evidently, it is common for groups to be offered the option of abbreviating their Last Degree trips when traveling conditions are poor. The option presented to us was to be dropped off at 89º20’ North, effectively reducing our trip from sixty nautical miles to forty. (Each degree of latitude consists of sixty “minutes” of one nautical mile per minute.) While we appreciated the offer (its intent was to assure that all groups would make it to the North Pole under their own power rather than being ignominiously plucked off the ice by helicopter), we unanimously concluded that we wanted to do the full degree. Miroslav fully supported our choice.

After the meeting we once again went outside and fetched canisters of fuel to load onto our sledges. We carried two gallons per man, a generously abundant supply intended to see us through the possibility of being stranded on the ice by bad weather. Thoroughly chilled, we dragged the sledges to the helicopter landing zone and awaited our chance to board. While doing this I got my GPS out and pegged Barneo’s location at fifteen nautical miles from the pole. Although it is always good practice to get a GPS waypoint for a location that you are going to return to, the logic diminishes when you are near the North Pole. The reason is that the sea ice is constantly moving and “here” today may be miles away tomorrow. One of the Barneo staffers mentioned that the drift this year is exceptional and that the entire base, huts, helicopters, runway and everything else, had moved seven kilometers in just the last day. Where it would be when we completed our expedition was anyone’s guess.

Our transport to 89ºN was a Russian MI-8 helicopter. It was an ugly beast with clamshell cargo doors in the back, a single five-blade rotor, twin 3,900 horsepower turbines and its sides blackened by its own exhaust. I had read somewhere that the MI-8 is the world’s most commercially successful helicopter based on the number of examples produced. They evidently have an excellent safety record, something I much appreciated.

For the trip to the drop-off point, fourteen expeditioners and four crewmen squeezed aboard the helicopter and with teeth-rattling vibrations and a feeling of limitless power the big machine clawed its way into the air, wheeled onto its chosen meridian and left Barneo in a storm of kicked-up ice particles.

The copter plowed ahead for forty minutes and then landed to disembark a group of seven guys who had elected to do the forty nautical mile journey. Once they were dropped off there was enough room in the helicopter for me to get to a window and observe the ice below.

…as far as the eye could see and evil-looking leads of open water stood out like black veins against the troubled white ice.

What I saw was not appetizing. The surface was seamed and buckled as far as the eye could see and evil-looking leads of open water stood out like black veins against the troubled white ice. It all looked like a giant jigsaw puzzle and it struck me forcibly that you could sledge for miles around these obstacles only to find yourself in an exit-less box. I wondered whether we made a mistake in choosing to do the full degree. Looking around the cabin of the helicopter I could see from the sober faces of my teammates that I was not the only one with doubts. It was probably a good thing that the din of the turbines precluded any conversation. I do not think that any of us would have found much encouraging to say.

We finally reached 89ºN at 10 pm. In a matter of minutes we had unloaded our gear and were watching the MI-8 beeline towards Barneo. We lost no time getting the tents up and the stoves humming. Miroslav proposed that we be outside our tents to break camp at 8 am the next morning.

Friday, April 6

On waking I unlimbered my GPS and was delighted to see that overnight we had drifted north 1.3 nautical miles. Thus, without exerting a particle of energy we were that much closer to our goal.

Unfortunately, that was the last bit of good news we had all day.

As per plan, we were all out of our tents promptly at 8 am and a quick poll revealed that everyone had a good night’s sleep. It took forty-five minute’s cold work to break camp, an unexpectedly long time that is bound to improve with practice.

We started out and for the first thirty minutes the ice conditions were not at all bad. I was thoroughly pleased with my borrowed skis and the exertion of skiing while pulling a 100 pound sledge had started to warm me up nicely. Then we hit our first pressure ridge and the good times faded abruptly.

Pressure ridges are formed when two immense sheets of sea ice collide. The sea ice is anything but homogeneous and, under the influence of tides, currents, winds and distant storms tends to split into pieces. The pieces can be many square miles in extent and they interact with one another with astonishing violence. When a floe containing millions of tons of ice smashes into another mega-million ton giant, the leading edges are shattered. The debris is both subducted and upthrust and, with the sound of a thousand cannons, the grinding continues until the inertial forces are exhausted. What is left is a twisted, irregular wall of ice blocks that may meander for miles across the frozen landscape. The blocks cover the range from refrigerator-sized to house-sized and everything in between. The challenge for the polar traveler is to find a way around or over these obstacles.

Upon confronting our first pressure ridge Miroslav led us parallel to it until he found a reasonable passage point. With the skill born of years of Arctic experience he quickly made his way over it. I happened to be next in line and resolutely started to clamber up. Halfway up I began to lose traction and leaned hard on my beloved carbon fiber ski pole to gain purchase. Disaster #1: the ski pole snapped. Disaster #2: looking down at the broken remnant of my ski pole I saw why I had lost traction…the skins had separated from my brand-new skis. Speechless with horror, I removed the skis and made it to the other side on foot.

Sasha and Roman made it over the pressure ridge without incident. Sibu, with his natural athleticism, made it as well but his half-skinned skis provided plenty of trouble in the process.

Since we carried no spare skis or poles, Miroslav reached into his bag of tricks and tried to conjure up a fix for my broken equipment. The obvious solution for the skis was to re-glue the skins. However, our repair kit did not contain any glue because Vicaar uses mechanically-attached skins instead of glued ones. What was left was to try to attach them with a series of compression straps. This initially looked promising but after a couple of minutes the skins were flapping uselessly and it was apparent that I would be walking for the rest of the day. Miroslav promised to have a second go at a fix after we reached camp later that day.

At first, the thought of walking to the pole and muddling along with one ski pole six inches shorter than the other horrified me. The nearly seventy miles that separated us from the pole seemed like an impossible distance. Fortunately, I did not have the luxury of dwelling on these thoughts. With the temperature at minus 20ºF you have to keep the train moving or everybody is going to freeze. So, we got on with it and I focused one hundred percent of my attention on just keeping up.

The ice conditions were absolutely chaotic with scores of pressure ridges and a surface that alternated between rock-hard ice and champagne powder. The areas of powder gave me fits because I post-holed up to my knees and only had one usable ski pole with which to extricate myself. The basketless broken pole was helpful for balance but only where the surface was relatively firm.

…Without preamble Miroslav’s left ski literally broke in half!

We made slow but steady progress for a couple of hours after my equipment Waterloo when it became Miroslav’s turn to be bitten in the neck. Without preamble his left ski literally broke in half!

A born tinkerer, Miroslav took this setback in stride and with compression straps, duct tape and a couple of wooden splints, fashioned a workable fix. I was dumbfounded that he even tried because the damage was so severe.

The terrible conditions were a strain on all of us. Our heavy sledges capsized repeatedly in the irregular terrain and brute force was needed to drag them up and over the pressure ridges. The ice that makes up pressure ridges is as hard as granite and we quickly learned that even tiny projections could hang them up, requiring they be lifted over the obstacle. Several times I tried to clear a path for my sledge by kicking away dainty-looking spurs of ice. I might as well have tried kicking a concrete foundation for all the good it did me.

We ground on for hour after hour, generally stopping for a break every ninety minutes or so. Finally, during the last two hours of the day conditions eased and we had the pleasure of traveling over gently undulating ice.

Ten hours and twenty minutes after starting, Miroslav consulted his GPS and determined that we had had enough fun for the day. We were all very grateful to unhitch ourselves from the sledges and call it quits.

With a day’s practice under our belts Sibu and I were a bit more efficient in getting the tent up and stove going.

It was wonderful to have the first day behind us. I took a GPS reading and found that we had made nine nautical miles of northward progress, which, when combined with the drift miles of the previous night put us on pace for a six-day trip to the pole. This was wonderfully encouraging.

I was also encouraged by the fact that my hiking pace allowed me to keep up with the group without any problems. I did not think it likely that the conditions ahead of us will be worse than today’s and it was cheering to hope that the worst may be behind us. Most surprising of all was that I found the idea of trekking to the pole compellingly attractive! I am not a particularly skillful skier and the need to tackle technical terrain on ski had always been on my horizon of concern pre-trip. Because of the equipment problem I am free to substitute an activity that I am extremely confident about (hiking) for one with lots of question marks. That is a pretty good trade even if it means that my Ski the Last Degree Expedition will be transformed into Trek the Last Degree one.

Saturday, April 7

The morning GPS reading showed that we had made 1.2 nautical miles to the good overnight. After reading numerous accounts of journeys where the ice was moving in the wrong direction (the “polar treadmill”) it was wonderful that we were having better luck.

Before we started out, Miroslav came to me with good news and bad news. The good news was that he fixed my broken ski pole. Using a few inches of a spare tent pole he was able to fashion an internal splint that fit snugly inside the hollow carbon fiber shaft of the ski pole. This and a couple of wraps of duct tape made the fix complete. “Stronger now than before!” said Miroslav. The bad news was that the skis were still hopeless.

Conditions could not have been better for the first four hours of the day. The sun was shining, the wind light and the temperature a comfortable minus 10ºF. I reveled in the use of my newly mended ski poles and with each step grew more confident about my ability to pull off a walk to the pole. Most importantly, there were fewer pressure ridges to contend with. While there were plenty of up-thrust areas they were not as jagged and steep as before. They evidently were the healing scars of pressure ridges from days gone by.

All of us, save Miroslav, made changes to our clothes today. Yesterday, we wore our down jackets all day long. Today, the Russians and Sibu used Gore-Tex windbreakers instead. I wore a polar fleece jacket and lightweight down vest. Comparing notes, all of us found that down mountaineering jackets were too warm and led to sweating while underway. Sweating is a big no-no in the Arctic because the instant you stop you begin to cool very fast.

One thing we all found impossible to use was ski goggles. No matter how careful we were to avoid icing, the inside lens always iced up within five minutes. Among us we had three different brands of high quality goggles, none of which worked at all. Presumably the high relative humidity caused by open lanes of water was to blame for the icing. However, the practical effect was that our goggle-less faces took a lot of abuse from the cold.

After four good hours the surface once again became disturbed. However, instead of phalanxes of pressure ridges, this time there was a combination of pressure ridges and open lanes of water (“leads” in Arctic parlance). Crossing the leads was tricky business because they meandered in all directions, intersected with each other and sometimes led to impassible cul-de-sacs that forced us to backtrack and try a different route. It was wearing to travel a substantial distance east or west or south just to get the opportunity of a bit of northward progress.

Another hazard was what Miroslav called “unsafe ice.” Immediately after an ice sheet splits apart the exposed water begins to refreeze. Sea water freezes at about 28ºF and it is not long before the whole mass is cemented together again. However, it can take a substantial amount of time for the ice to refreeze to a thickness that is safe to travel over. “Unsafe ice” is literally thin ice.

…It was like a slow-motion car crash. I distinctly remember seeing the ice give way under my left foot and the inky black water rushing toward me as I fell.

At about 5:30 pm I was traveling over an area of new ice that Miroslav judged to be safe. During the course of the last few hours we had passed over dozens of these without incident. Miroslav, Sasha and Roman had already crossed and were waiting on the other side. Eighteen inches from the junction where the young ice met the old I put my foot down and abruptly plunged into the Arctic Ocean. It was like a slow-motion car crash. I distinctly remember seeing the ice give way under my left foot and the inky black water rushing toward me as I fell. It was as if a trapdoor had opened under my feet. Momentum carried me forward and I luckily caught my elbows on the ledge of old ice that rose six inches above the water’s surface. With the fall arrested I pulled myself out before my boots had a chance to fill with water. I dragged my sledge onto the safe ice and took stock.

Happily, I discovered that I was perfectly fine. The water on my outer garments froze within seconds and was easy to knock off. The two capilene under-layers on my legs were soaked but I still felt reasonably warm.

Miroslav asked whether I wanted to call it a day and get into the tent to dry off. I said “No” with the only proviso being that we make no rest stops until the end of the day. So, off we went, thankfully without any further swims along the way.

On arriving in camp at 7 pm everyone pulled out all the stops to help get me in my tent quickly. In short order I was inside with both burners of the stove going, a change of clothes and my wet garments drying on the netting. After a hot meal and a couple of cups of tea I felt like a new man.

Early in the day Miroslav told Sibu and me that he would visit our tent that evening for some sort of surprise. True to his word, at about 11 pm he came in, guitar and harmonica in hand, and serenaded us for the next hour. He is actually a very talented musician and singer. The night before we had heard him performing for his own pleasure in his tent. He said that he brings his instruments on all of his trips. His guitar is a collapsible type with a detachable neck.

Thus ended an eventful day, always to be remembered, by me at least, as the day I went swimming in the 14,000 foot deep Arctic Ocean. We were on the march for nine hours and forty minutes and made an outstanding 9.2 nautical miles of northward progress.

Sunday, April 8 (Easter Sunday)

The morning GPS reading showed that the polar conveyor belt was still working in our favor, this time to the tune of a third of a nautical mile.

Prior to starting out for the day Sibu gave an interview to a Johannesburg radio station via satellite phone. His sponsor’s publicity team has been in contact with him regularly throughout the trip and has been collecting sound bites and arranging a full agenda of interviews in anticipation of his arrival at the North Pole a few days from now.

It was terrific to watch Sibu in action during the interview. He is wonderfully articulate, modest and relatable. He was able to convey the essence of what it is like to sledge over the sea ice (cold, hard, unremitting work!) in a way that communicated the difficulties but emphasized the joy of striving for a worthy goal. His happiness about being in this strange and rarely visited place shone through and no doubt inspired the listening audience, warm in their homes on Easter morning, to pray for his success and safe return. His sponsor should be well pleased.

Upon emerging from the tents we saw that the fine weather of the past days had deserted us. It was cloudy and noticeably damp with a nasty cold breeze and intermittent snow.

Almost immediately we ran into a heavily disturbed area of pressure ridges and open leads of water. The leads were ominous-looking, with a slushy skim of ice covering the black-green sea. They thwarted our progress in a most discouraging way because each required a lengthy scouting expedition to find a place narrow enough to cross. We no sooner crossed one than the next barred our way. I admired Miroslav’s skill and persistence in finding our way through the maze. However, it was more than apparent that our northward progress for the day was not going to be good.

At a break at 11 am I pulled out my camera to take a few pictures and had a chance to get a close look at my teammates. All looked like snowmen with giant icicles hanging from eyebrows and lashes. Every square inch of their clothing was rimed with snow. We all quickly decided that this was a wonderful photo-op and took pictures of each other to show to friends back home and impress them with our great suffering on the trip. However, the truth of the matter was that we were all feeling fabulous and that the bad weather made the adventure all the more piquant.

…we had yet another equipment failure. This time, poor Miroslav’s remaining “good” ski broke in half.

We continued to soldier on amidst the pressure and leads until 1 pm when we had yet another equipment failure. This time, poor Miroslav’s remaining “good” ski broke in half. He manfully tried to fix it but his efforts were doomed because we had no more wooden splints to brace it with. As a last resort he borrowed one of my skis and muddled through with it until the end of the day. We had to make numerous stops for him to re-attach the skins but with his skillful technique, Miroslav was able to make the mismatched pair work.

A full ten-hour day on the ice netted us just eight nautical miles of northward progress. Given the deplorable conditions, this was a respectable total but still a bit of a letdown. We all knew that we had a chance of reaching 89º 30’N today, the halfway point of our journey, and it was frustrating to end the day a mile short of that goal.

On the physical side of things our entire party is doing well. Sasha pulls his heavy sledge as if it weighed nothing. His ability to manhandle it up and over pressure ridges is thoroughly impressive. Roman has become the star skier of the group and his prowess has improved remarkably since our first outing on Svalbard last week. He is very fit and our ten-hour days do not faze him in the least. Sibu also looks like he could keep going forever. He is a font of good spirits and his mind is unclouded by the slightest doubt that we will reach the pole. His physical reserves are such that nothing short of Armageddon will keep him from his goal.

As for me, I am feeling astonishingly well. I am enjoying the sledging life and walking to the pole feels like the most natural thing on Earth. While on the march I feel wonderfully strong. Nothing hurts, my spirits are high and I absolutely love being here. The experience of being on the sea ice thirty-one nautical miles from the pole on Easter Sunday is something I will treasure for the rest of my life.

Monday, April 9

Upon waking I discovered that we had drifted another four tenths of a nautical mile to the good. This brought us tantalizingly close to the halfway mark and we struck our tents with happy hearts. The sky was clear but without an insulating blanket of cloud it was murderously cold.

Conditions were challenging from the outset. The open leads of water were gone but row after row of pressure ridges stood in their place. In between the pressure ridges there was a choppy sea of ice waves that held unexpected pockets of deep, soft snow.

The pressure ridges slowed our progress considerably. Each one had to be climbed and the sledges capsized with depressing regularity. On the bright side, it was apparent that those of us who were traveling on foot had an advantage over those on ski. Sibu had put aside his traction-less skis yesterday and, like me, found negotiating the pressure ridges on foot relatively straightforward. Despite the fact that his sixty-five day ski trek to the South Pole gave him more skiing experience than most people get in a lifetime, he cheerfully noted that he is a “bush boy” at heart and that for him skiing is still a highly unusual activity.

Another cause for our slow progress was that Miroslav had an untold amount of trouble with his skis. He had started the day wearing my skis and they repeatedly disappointed him. He was persistent in trying different combinations of straps, duct tape and pleas for divine intervention to keep the skins in place but could not find a satisfactory solution. I am certain it wounded his pride to do so but at 2 pm he finally gave up on the skis and went on foot. This was good news for all of us because it was agonizingly cold standing around while successive remedies were applied.

We plowed on until we hit the ten-hour mark. After getting the tents up nobody was surprised when the GPS showed that our efforts had netted us only eight and a half nautical miles of polar progress. But, against that we had a lot to be happy about because we had chinned the halfway bar in only three days of travel, everyone was healthy and everyone’s spirits were high. During the day, Sasha paid me a big compliment. After I had bulled my way over a particularly nasty pressure ridge, he smiled and said, “Tom, you go like tank!” In truth, by that point I felt so good that I was beginning to think that I was born to trek to the pole.

My inadvertent dunking a couple of days ago produced an unexpected benefit for Sibu and me. We learned that you can make the tent toasty warm by just leaving the stove on for a couple of hours after dinner. We took stock of our fuel supply, compared it to our consumption rate and were delighted to conclude that we could be positively profligate in our use without the slightest hazard of running out. Ever since Saturday we have had the warmest tent on the Arctic Ocean.

Our domestic life in the tent is simple and uncomplicated. Sibu usually finds a block of old ice and chips off enough to meet our needs for dinner and breakfast while I get the stove going. We have a big kettle and prime it with water left over in our thermoses. We put the kettle on the stove and keep adding ice until it is full and the water boiling. At that point we pull out our insulated mugs and enjoy the indescribable pleasure of a hot drink. Dinner soon follows and while it is cooking we snack non-stop. Sledging does wonders for the appetite.

Vicaar has provided us with outstanding food packages. They are marvelously complete and each one contains a full day’s worth of breakfast, snacks, dinner, teas, instant coffee and condiments. There is instant oatmeal for breakfast, a huge freeze-dried package of stew or pasta for dinner and candy bars, nuts, cheese and dried fruit for in-between. It is wonderful to be able to pull a single bag from your sledge at the end of the day and know that all of your nutritional needs for the next twenty-four hours are covered. Simple is better!

After dinner and drinks we converse, write in our diaries and brilliantly find solutions for all of the world’s problems. Sibu regularly dictates a capsule summary of the day on a digital recorder. His summaries are always on point and delivered with admirable poise. He has that indefinable “it” factor that makes him a star. It seems inevitable to me that I will one day read in the newspaper that he has been elected President of South Africa.

Tuesday, April 10

We started the day with yet another boost from the polar conveyor belt. Our peaceful sleep yielded close to a full nautical mile of northward progress.

During the day our progress was phenomenal. For the first time this trip the ice was blessedly free from pressure ridges and open leads of water. Instead, it resembled a storm-tossed sea instantly flash-frozen. There were thousands upon thousands of snow waves to ascend and descend but all could be negotiated without the time-consuming delays that pressure requires. It was infinitely cheering to look ahead and see long stretches without big obstacles barring our progress.

Because going was easy and the day was bright and sunny, I paid attention to navigation for the first time and was dumbfounded to find that we were going in the wrong direction. Let me explain: at 9 am when we started out I noticed that my shadow was on my right side. This meant that the sun was on my left side and that led to the startling conclusion that we must be going south. After all, the sun rises in the east and if it is on your left (east) side at 9 am that has to mean that you are traveling south!

In the strange world that is the Arctic in April the sun shines twenty-four hours a day. It circles the sky at a low distance above the horizon and never ascends or descends much during the day. Day and night are indistinguishable and the only thing that allows you to differentiate one from the other is what your watch tells you.

I knew that Miroslav was navigating by GPS so despite the physical evidence to the contrary I knew that we must be tracking north. Given that, the only possible explanation for the sun being on the “wrong” side was that my watch was wrong. But how could my watch be wrong? It seemed to be working perfectly and was in agreement with everyone else’s watches. It turns out that the answer was simple.

For the whole trip I had been paying close attention to our latitude but completely ignoring longitude. At a break I pulled out my GPS and saw that we were at 167º East longitude. Our watches were set to Longyearbyen time and Longyearbyen is at 15ºE. The 152º spread between Longyearbyen’s longitude and ours meant that the local time at our location was a full ten hours later than what our watches were telling us. (Time zones change in 15º increments.) Mystery solved! Thus, 9am Svalbard time was really 7 pm local time and at 7 pm the sun would most definitely be on your left if you were heading north.

We put in a full ten hour day and were rewarded with a best-ever eleven nautical miles of northward progress. At the day’s end we were at 89º50’N, just ten nautical miles short of the North Pole. Everyone was confident that tomorrow we would reach the pole and was elated when Miroslav reported that he had talked with Barneo and that our pick-up would be delayed until the day after our arrival at the pole.

The thought of overnighting at the pole was absolutely thrilling and we went off to sleep with that happy thought in mind.

Wednesday, April 11

The morning GPS reading showed that we had gained one nautical mile towards the pole overnight. That was a perfect start to a day that turned out to be one of the most difficult of the entire trip.

Yesterday’s benign conditions were replaced by icy chaos. Instead of long stretches of open terrain we could never move more than a few yards without having to climb through a new wave of pressure. In addition, there was much more soft snow than before. Miroslav had a bad moment when he fell up to his crotch in a hidden hole and hurt his leg. He limped for the rest of the day.

…It took us two excruciating hours to make those paltry three kilometers but at 5:30 pm the GPS read 90ºN and the goal was reached.

We ground on for hour after hour and at 3:30 pm the GPS told us that we had only three kilometers left to go. It took us two excruciating hours to make those paltry three kilometers but at 5:30 pm the GPS read 90ºN and the goal was reached. It took a few minutes for the reality of the accomplishment to sink in. In a perverse way I think that we were all rather happy that we had to fight so hard on our final day to get to the pole. Eight and a half hours of grinding work made finishing all the more sweet.

As luck would have it, we did not have much time to savor our victory because as we were approaching the finish line we saw a MI-8 helicopter heading in our direction. It settled onto the ice a quarter mile from the pole and we saw that another group was boarding. It turns out that the big seven man team that was dropped off forty nautical miles from the pole only beat us there by about four hours. Since the chopper had room for everyone we had to shelve our plan for overnighting at the pole.

I think we had about a half hour at the pole before being whisked away by the helicopter. To be honest, after freezing our hands taking pictures of each other the chopper looked pretty good and Barneo beckoned as a bastion of civilized comfort. As usual, the helicopter was jammed to the rafters.

It only took twenty minutes to reach Barneo. I logged its position on my GPS and saw that it was now twenty miles west of where we had left it seven days earlier. Immediately after getting off the helicopter I was interviewed by a German radio reporter who was curious to learn why anyone would willingly spend lots of money to be tortured by cold and fatigue for days on end. Good question!

Barneo staff pointed us to the huts that served as dormitories and told us to grab any open bed. The huts each housed twelve people and, after a week in the wild, looked fantastically comfortable. Everybody got his own cot and the inside was heated to a tropical 50ºF. We were then treated to a big meal, had all the coffee and sweets that we could handle and by 10 pm toddled off to bed. It was incredibly nice to drift off to sleep in the warm hut with the trip to the pole successfully accomplished and all doubts resolved.

Thursday, April 12

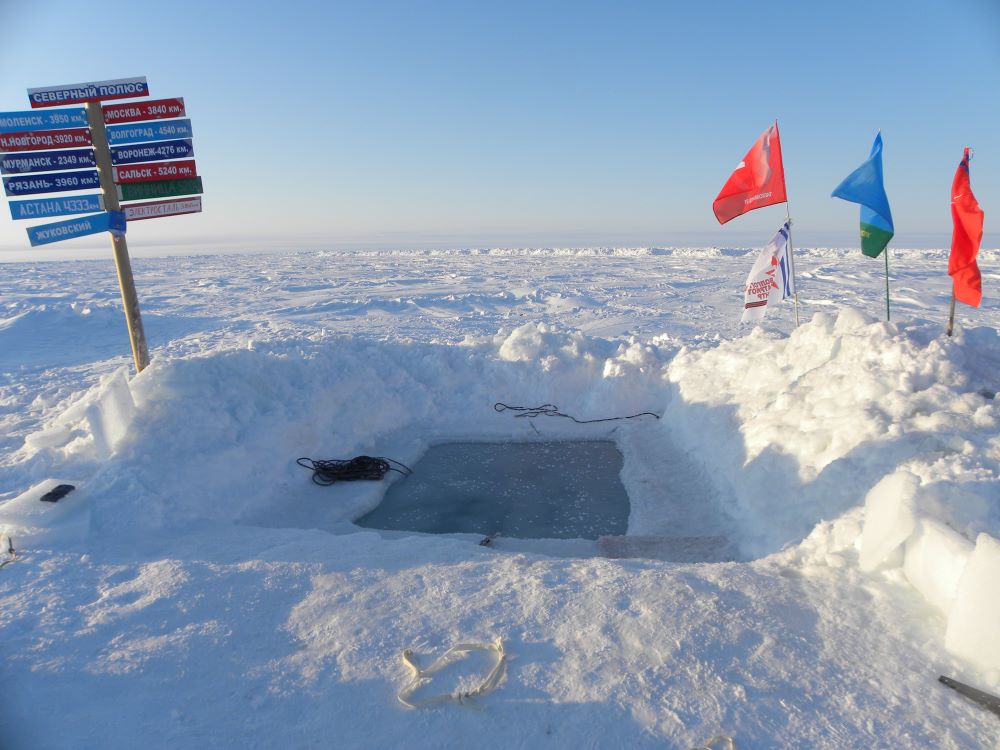

We all slept late and took the opportunity of doing a little sightseeing around Barneo. There were a dozen or so sled dogs as the star attraction and they were an engagingly frisky bunch. Also, there was an area where a six-foot square “swimming pool” had been hacked out of the ice.

…To prevent the possibility of someone disappearing under the ice, all swimmers are tied to a safety line manned by two sober observers.

Evidently, many people consider a trip to the North Pole incomplete without a dip in the Arctic Ocean. Since I had already checked that box I was not tempted to do an encore. One of the Barneo staff told me that no one ever uses the swimming pool without first fortifying himself with a liberal amount of Russian vodka. To prevent the possibility of someone disappearing under the ice, all swimmers are tied to a safety line manned by two sober observers.

At 1 pm the Antonov touched down on the ice runway. We loaded our sledges aboard, grabbed seats and two and a half hours later arrived back in Longyearbyen. After mustering out at the hangar we reclaimed our hotel rooms. It felt absolutely spectacular to take a hot shower, change into regular street clothes and return to the modern world of high speed internet, satellite TV, central heat and indoor plumbing.

We all gathered in the Radisson’s beautiful dining room at 7:30 pm for a meal and Vicaar’s “Polar Diploma” ceremony.

Refreshments flowed generously and most of us got into the spirit of the Arctic by ordering the “Traditional Svalbard Feast” which featured whale, seal and reindeer meat.

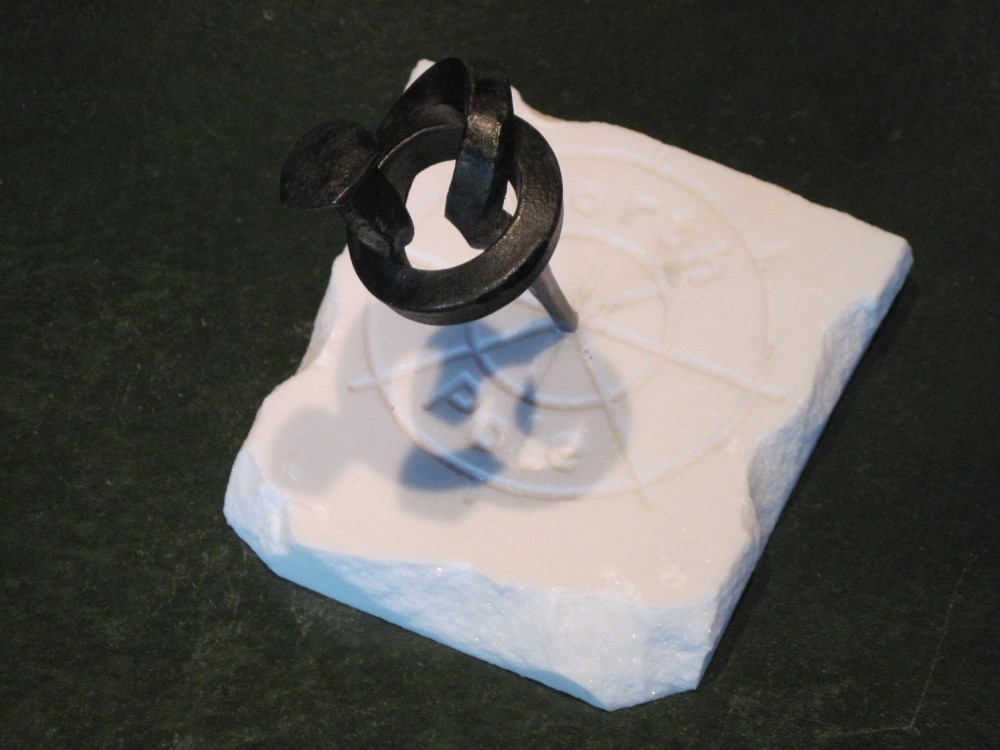

A good time was had by all and we genuinely appreciated Vicaar’s thoughtfulness in presenting us with certificates memorializing our arrival at the pole and handsome “Big Nail” trophies. In Eskimo tradition, the furthest point north was conceived as a giant iron nail piercing the ice. The trophies captured the tradition marvelously. We partied late into the night.

April 13-16

Our unexpectedly fast dash to the pole left all of us with a couple of extra nights in Longyearbyen. We used them well with two more hilarious group dinners and local sightseeing. Unfortunately, no one ever got a glimpse of a live polar bear and we had to settle for photos of ourselves mugging with various stuffed ones around town.

…One thing is for certain: polar guides are made from stern stuff!

We said our final goodbyes on April 15 with Sasha and Roman heading back to Moscow, Sibu to Johannesburg and me to Houston. By this time we were all firm friends and sorry to have to part company. Miroslav said that he was going to stay around on Svalbard for a while, possibly to ski solo out into the backcountry for a few days. One thing is for certain: polar guides are made from stern stuff!

On the transatlantic flight home on April 16 the plane overflew the southern tip of Greenland. It was fascinating to see the great ice cap rising from the rocky shoreline and stretching limitlessly north. The sea was positively cluttered with icebergs. That got me to thinking. Greenland!!! Then I looked down at my puffy, frost-nipped fingertips. I decided to wait a while before deciding on my next adventure travel destination.

When I arrived in Houston the weather was typical, 85ºF and humid. The sheer novelty of being effortlessly warm was wonderfully entertaining for days afterward.

Photo credits: Many thanks to Sibu, Sasha, Roman and Miroslav.