50 Mile Challenge

Origins of the 50 Mile Challenge

During the winter of 1963 a new fad swept America, the 50-mile hike. It was one of those things that came out of nowhere but suddenly everywhere with a barrage of press coverage and television reports on the nightly news. With a spontaneity that defied explanation thousands of people abruptly decided that walking 50 miles was a good idea and took to the roads. In the context of the times this was extraordinary. Marathon racing was then on the outer fringes of sporting endeavor and generally regarded with the same disinterest as, say, swimming the English Channel. For people to suddenly spark to the thought of roughly doubling the marathon distance powerful forces were in play. What was going on? It can be summed up as follows:

Masterful Persuasion—John Fitzgerald Kennedy was President of the United States and an outspoken advocate for physical fitness. Just prior to his inauguration in 1961 he wrote an article in Sports Illustrated magazine, “The Soft American”, where he bemoaned the current state of our fitness and outlined a plan for bringing it up to a higher standard. This planted a seed that made many Americans think of physical fitness as a worthy national goal. And, in keeping with the principle “Ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country” that he announced in his inaugural address, people began thinking of fitness as a patriotic duty.

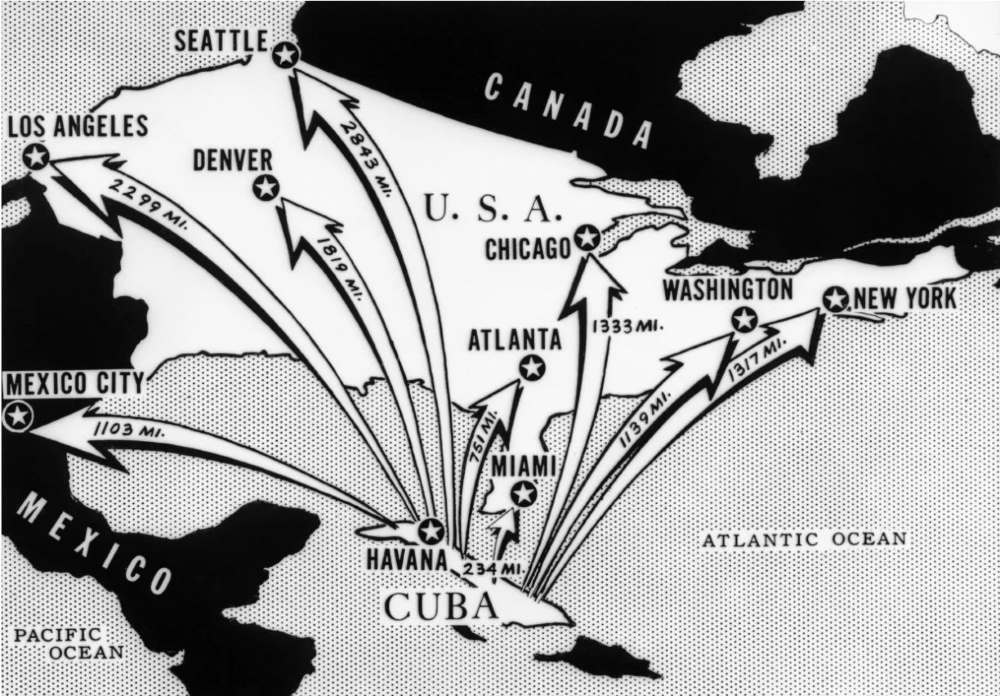

A Step Back from the Precipice—Late in 1962 the Cuban Missile Crisis played out and brought the world as close to nuclear war as it has ever been, before or since. Shortly after discovering what he described as “unmistakable evidence” that the Soviet Union had armed Cuba with long range ballistic missiles, Kennedy deployed American warships to blockade the island and prevent Russian ships carrying nuclear contraband from landing. He demanded that the missiles be removed and cautioned his Soviet counterpart, Nikita Khrushchev, “to correctly understand the will and determination of the United States” to see to it that the missile threat be eliminated. The clear message was that all-out nuclear war could ensue if the crisis was not resolved. For thirteen days in October of 1962 the world teetered on the brink of annihilation but ultimately the Russians agreed to bring their missiles home.

Resolution of the crisis literally made Americans feel they had been reborn. The terrifying prospect of war, death or life in a post-apocalyptic wasteland was replaced with a sense of optimism. Just as the approach of New Year’s Day inspires people to make resolutions to correct bad habits or otherwise improve themselves, deliverance from the dreaded nuclear holocaust gave many Americans the sense that they had been given a second chance to live a better life. The “I should have…” and “If only I had…” thoughts that occupied people during the crisis suddenly became things to act on. Among the things people decided to do was to start exercising more and recapture the fitness they imagined would give them happier, healthier lives.

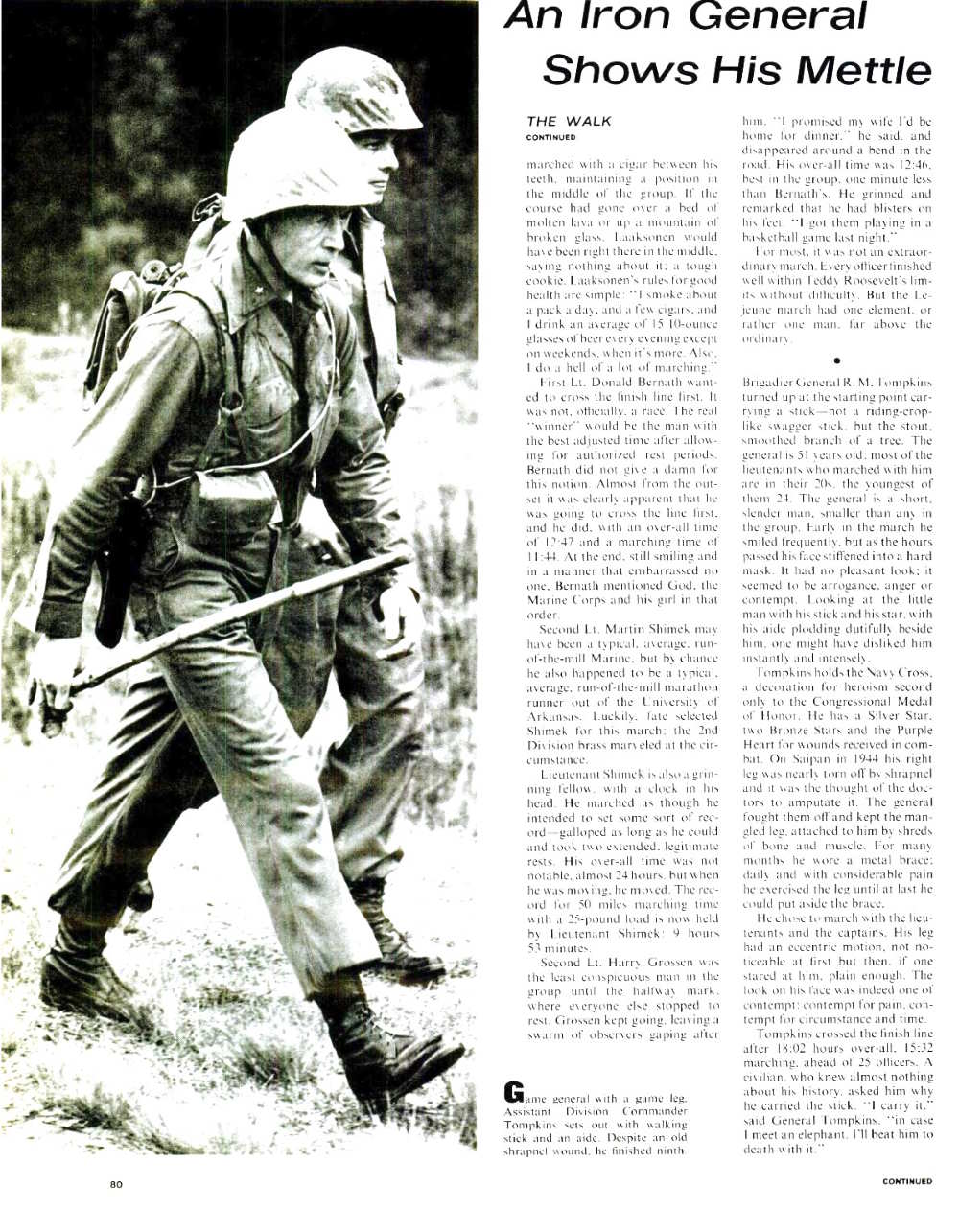

A Concrete Goal—History does not recall who among the White House staffers discovered it but in January of 1963 a 1908 Executive Order from Theodore Roosevelt’s administration was unearthed and brought to President Kennedy’s attention. The Executive Order required all Marine captains and lieutenants to demonstrate that they could hike 50 miles in 20 hours or less over the course of 3 days. Fresh off the massive troop mobilization that accompanied the Cuban Missile Crisis, JFK thought it a splendid idea to demonstrate that today’s soldiers were equal to the challenge undertaken by their 1908 predecessors. He arranged for Marine Commandant David Shoup to announce the challenge and select the first group of officers to carry it out. This was done and on February 12, 1963, a group of 34 Marine officers led by Brigadier General Rathvon M. Tompkins set out from Camp Lejeune, North Carolina to begin the march.

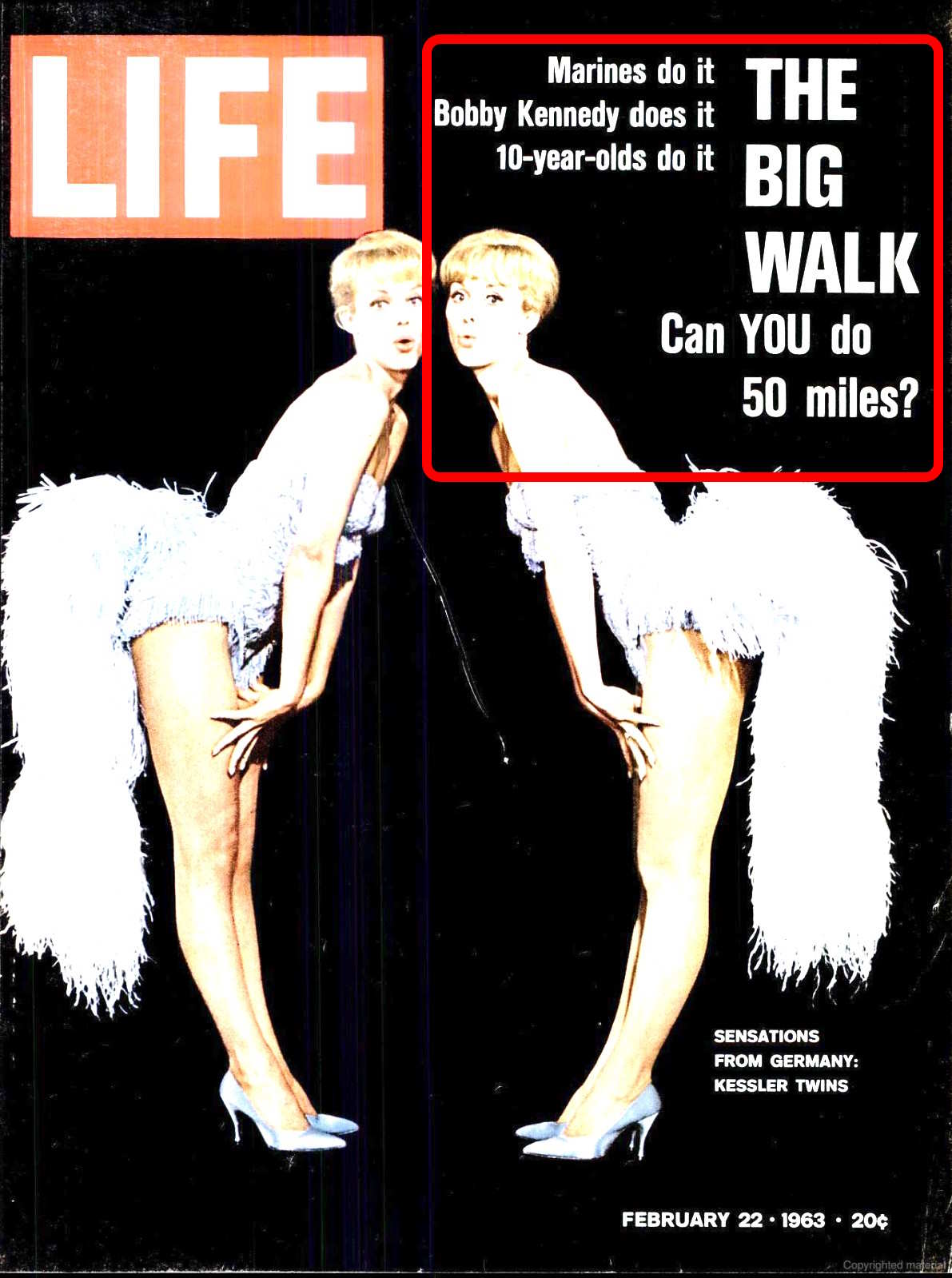

Press interest was huge and in the short interval between the announcement and the date of the first “official” 50-mile hike hundreds of soldiers and citizens jump-started the challenge by setting off on hikes of their own. While the White House expressly cautioned that this was meant to be a test for the military alone, members of the public eagerly embraced it as their own. The timing was perfect: having been saved from nuclear doom and freshly resolved to live life to the fullest, everyone in the country now had an unambiguous goal with which to celebrate their deliverance. Overnight the 50 Mile Challenge became a craze.

Powerful forces!

For the 14-year old me at the beginning of 1963 the 50 Mile Challenge represented a first-class adventure. Although I had never so much as hiked more than three or four miles at a time in my life, the Challenge seemed ridiculously easy. After all, it involved nothing more complicated than walking! My confidence was bolstered by the fact that I had read the February 22, 1963 Life magazine article, “The Big Walk”, chronicling the 50-mile hike phenomenon and picturing people from one end of the country to the other on the march. It covered the trek led by General Tompkins and his Marines as well. In a biographical sidebar, the magazine reported that the good General was 51 years old and that he completed the hike in a little over 18 hours. It struck me forcibly that if anyone so incredibly ancient as 51 could complete the Challenge there was absolutely no reason why me and a group of my friends could not knock it off. All we needed was to figure out a route, lace up our sneakers and go. On completion of the walk I was certain that my friends and I would be applauded for our patriotic demonstration of fitness, get our names in the papers and that President Kennedy would be reassured to learn that today’s youth was not so soft as he had thought.

Unfortunately, upon hearing of our intention to do the Challenge some of the parents of the guys in our group vetoed the idea. They argued that we had no idea of the magnitude of the event (True), that someone would probably get run over by a car (Overly-dramatic) and there was no way that any of them would spend 20 hours in a van supporting our trek and picking up stragglers (Bingo! The real reason). For us it was game over!

Then, on November 22, 1963, just nine months after Life magazine published “The Big Walk” article, JFK was assassinated in Dallas. An era abruptly ended and with it the notion of hiking to celebrate life and improve the nation died as well. Harsher realities came to the fore and Americans were vulnerable once again.

Flirting With Long Distance

I gave not a moment’s thought to long distance hiking or running for the next sixteen years. However, in 1979, together with a group of friends from work I decided to try running as a sport and immediately decided to do a marathon as the ultimate goal for my training. My enthusiasm for running was a product of the times. Jim Fixx had written his seminal “The Complete Book of Running” a couple of years before and a new fitness boom was sweeping the country. The marathon emerged from the shadows to become a thing every self-respecting athlete had do at least once in his life. Six months and 765 dreary training miles later I accomplished the goal. I managed to complete the Newport (Rhode Island) Marathon in 3:23:20. I so much enjoyed the experience that I waited until 2007, 28 years later, before doing my second marathon. That trip up and down Pikes Peak is chronicled here.

It was not until 2015 that I finally exceeded the 26.2 mile marathon distance. On two consecutive days while traversing the Greenland icecap the team of skiers I was a part of covered 27 miles per day. We were highly motivated to do the distance. An arctic hurricane was brewing and on May 28, 2015 we skied 27 miles to a point where we hoped helicopter evacuation would be possible. Unfortunately, by the time we reached that point, the leading edges of the storm made evacuation a non-starter. We had no choice but to hunker down in our tents for a few short hours before continuing into the teeth of the violent storm that was just the opening act to the awful monster growing in its wake. We skied 27.3 miles in 13 harrowing hours to reach safety at the coastal village of Isortoq. After 24 days on the icecap we completed the Crossing of Greenland with that final push. It was not until a few weeks later that I reviewed our GPS logs and discovered that May 29, 2015 was the biggest mileage day of my life. It was almost the longest-duration athletic performance of my life as well, exceeded only by my 14-hour summit day on Aconcagua back in 2001. My trip reports on Greenland and Aconcagua are here and here, respectively.

Making the “Go” Decision

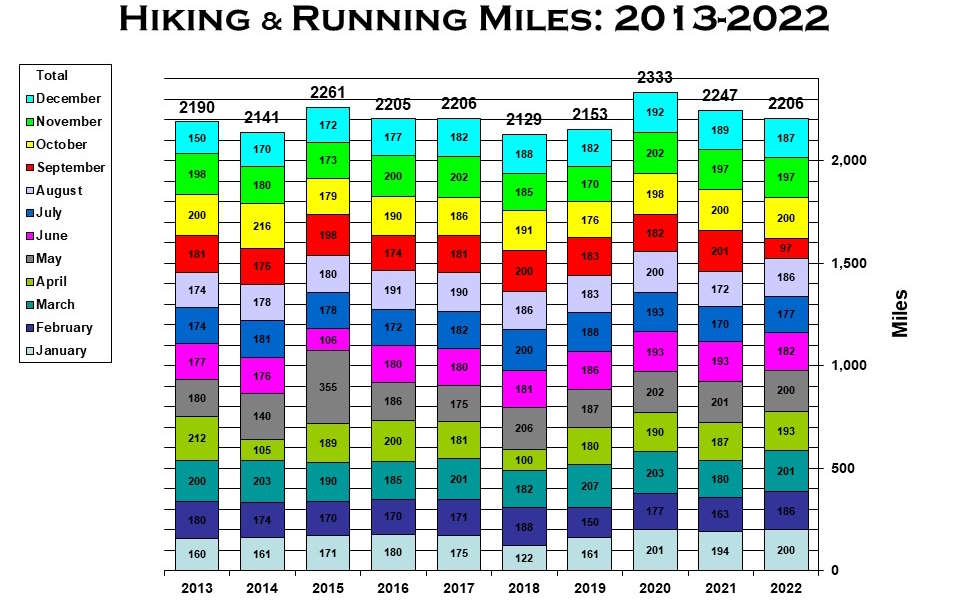

While not being a marathon or ultra-marathon kind of person, I have been diligent over the years of hiking or running nearly every day. Over the past 25 years I have amassed nearly 50,000 miles, averaging just under 2,000 miles per year. In the last 10 years I have upped the ante averaging 6 miles per day or 2,200 miles per year. In the beginning of 2023 those numbers encouraged me to start thinking big. I thought it would be fun to resurrect the 50 Mile Challenge of my youth and see whether I could complete the distance 60 years after first considering it. Needless to say, my parents were no longer around to stop me! Also, lurking in the back of my consciousness was the foggy memory of that 1963 Life magazine article and its photograph of General Tompkins leading his troops to the finishing line. Ultimately, it was that half-remembered picture of General Tompkins that convinced me to do the hike.

Planning the Route

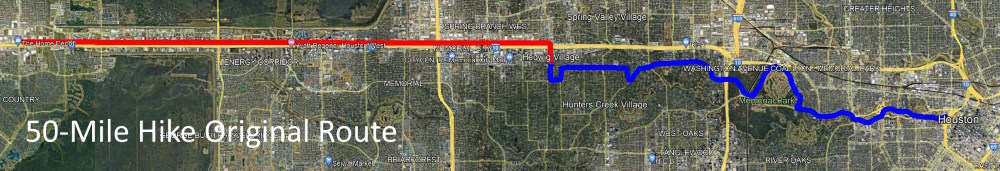

Early on I decided that I would do the trek in the vicinity of my home in Houston, Texas. While the idea of doing it on a leg of the Appalachian Trail or John Muir Trail was attractive, simple was better. It took no time at all to construct a route in Google Earth that took me 12.5 miles west of my house and after returning home 12.5 miles east into downtown Houston and back again. Every inch of the route was on sidewalks or established running paths. An added topographical bonus was that Houston is pancake-flat and there was not a single hill to climb on the whole route.

Hitting the “Go” Button

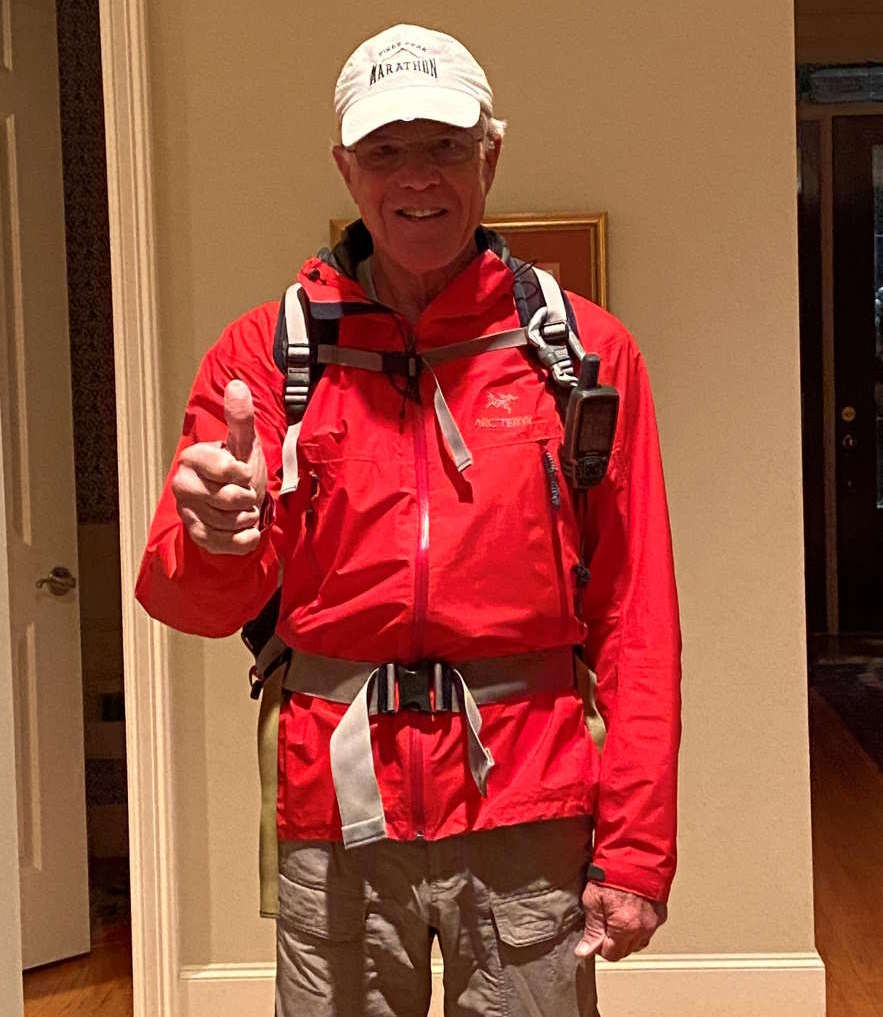

On February 14, 2023, sixty years and two days after General Tompkins set out on his 50-mile hike, I set out on mine. I started at 4:35am full of good spirits and completely confident in my ability to measure up to the Challenge. While I knew that rain was in the forecast, I did not think it would hamper my efforts materially. Here is the summary of my hike:

Leg 1: 12.5 miles due west

As predicted, the rain started nearly the first moment I stepped out the door. Still, it was exciting to be off and I was pleased that my trekking clothes were comfortable, time-tested veterans that would keep me snug and reasonably dry. My backpack was a featherweight 10-pounds since all I needed to haul was food, water and some extra clothes. About three wet but uneventful hours after starting I hit my 12.5-mile turnaround point. I was grateful to be able to reverse direction and begin the long slog towards home. A few minutes later I stopped for my first rest break of the day at a local restaurant. It was wonderful to get out of the rain and warm up with a mug of coffee and a snack. When I reached that welcome oasis I was 13.08 miles into the hike and my elapsed time was 3:12:58. I had covered the distance at a respectable 14:45 per mile pace.

Leg 2: Due east to halfway point

Rejuvenated after my 23-minute rest and refueling break, I attacked the hike back home in good spirits. I was tired but (I rationalized) who wouldn’t be after more than three hours on his feet? I was encouraged to be travelling over now-familiar ground and it was nice to be able to see landmarks that had been hidden by the pre-dawn night on my outbound journey. The only negative was that for the next two and a half hours the rain went from bad to worse. I finally reached home, my halfway point for the 50 Mile Challenge, at 11am, six hours and twenty-five minutes after starting. My elapsed time for the leg was 2:54:59, an excellent 14:19 per mile pace.

I took a lengthy 46-minute rest break at home and used the time to change out of my thoroughly soaked clothes and squishing shoes. It felt great to sit down, eat a light meal and feel warm and dry. The comforts of home were such that I decided on an impromptu change of route. Rather than doing the 25-mile remaining distance as a 12.5-mile out-and-back into downtown Houston, I thought it better to break it into three bite-sized chunks on routes I was thoroughly familiar with. Among the standard hiking routes I do nearly every week are a 10-miler, 8-miler and 7-miler. Each starts and ends at my house. I reckoned that the miles would seem to go faster if I was on familiar ground and it was comforting to look forward to a stop at home after each route segment.

Leg 3: 10-mile standard route

The good news was that the rain had finally ended and I could look forward to hiking in dry clothes. The less good news was that I was tired and knew that it would be another two-and-a-half hours before I could sit down again. My practice is to go continuously to on short (10 miles or less) hikes. I followed that do-or-die gameplan and finally completed the trek at a worryingly slow pace of 15:06 per mile. I was very, very tired at the end of it.

On arriving home, I rethought my route plan to compensate for my flagging energy. Instead of doing a 8-miler and a 7-miler to finish the Challenge, I would do a 7-miler and two 4-milers. This would give me an extra rest break and allow the two finishing legs to be done on the shortest and easiest route in my repertoire. After logging 35 miles on my legs, I was frankly exhausted and grasping at straws to find a way to the finishing line. I rested for 44-minutes before setting out on the next 7-mile segment.

Leg 4: 7-mile standard route

Despite feeling decidedly ragged when I left the house I was buoyed by my choice of route. The particular 7-miler I had chosen to do was one of my favorites. In any given year I would do it between 60 and 70 times, sometimes carrying a 50-pound pack. It was a hike I considered so easy that I would often do it as a reward for having done a tougher route the previous day. Easy peasy!

Not.

The mile markers came and went but with exquisite slowness. The friendly, trivial distance of a mile transformed into an endless measure of my fragile willpower. My pace deteriorated from the worrying 15:06 of the previous leg to an alarming 15:56 per mile. By the time I made it home a bit before 5:00pm I was twelve hours and eighteen minutes into the hike. A total of 42 miles had disappeared under my legs but I had no idea where I would get the strength to do the remaining 8 miles. I was baffled and discouraged. In planning the 50 Mile Challenge I had carelessly reckoned that I would complete it in 14 hours. I counted on a 15 minute per mile moving average (12:30:00 total) plus one and a half hours of break time. That goal was now out of the question. While my average moving pace of 14:54 per mile was within specifications, I had already spent 1:53:03 of resting time and was looking at the possibility that my pace on the final 8 miles would deteriorate to 20 minutes per mile. I was not a happy camper.

In the end my exhausted body called the final shot. Ten minutes into the break I developed the chills and my legs started to cramp. It was game over and my attempt at the 50 Mile Challenge ended in failure.

Failure “Yes” or Failure “No”?

From the charitable perspective of the 50 Mile Challenge as originally defined in President Theodore Roosevelt’s 1908 Executive Order, I successfully completed the Challenge. How so? The Executive Order gave soldiers 20 hours to complete 50 miles over the course of three days. Purely by coincidence I did an 8-mile training hike the day before setting out on my abortive 50-miler. Thus, I actually completed the Challenge with a day to spare. However, this legalistic technicality aside, I know I flunked the test I set out for myself. In retrospect, I am a bit disappointed. I made a good decision to quit when I did. But, a few hours later, I had a clear opportunity to complete the Challenge and passed on the opportunity. After going to bed, I woke up at 1:30am and was encouraged to note that I had no aches or pains and was feeling great. It immediately struck me that I could get up, do an easy 8-mile hike and finish all 50-miles of the Challenge within 24 hours of starting it on the previous day. Not wanting to seem like a maniac and still smarting from the collapse of my original plan, I went back to sleep. I wish I had swallowed my pride and gone ahead and done those final few miles. One very good reason for my regret is now I have to face doing the whole thing all over again! Grrrrr….

Looking on the bright side, 42 miles is now my lifetime best hiking mileage day. This is fully 15 miles better than I have ever done before. I gave it a good shot and it is entertaining to speculate on how the 14-year old version of me would have done if he had gotten the opportunity to do the Challenge all those years ago. My guess is that 14-year old Tom’s performance would have made me proud.