Mt Whitney to Death Valley

Mt Whitney to Death Valley High-Low Expedition

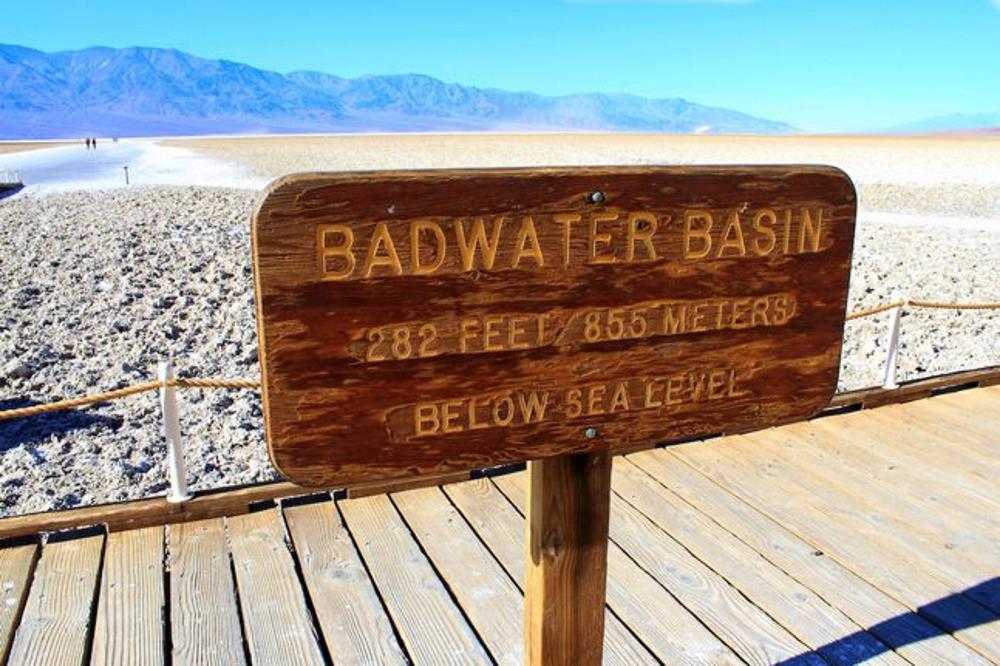

Standing 14,505 feet tall, Mt Whitney in southern California is the highest mountain in the lower 48 states. Badwater Basin in California’s Death Valley is an amazing 282 feet below sea level and is the lowest point on the entire North American continent. Astonishingly, the two points are only 85 miles apart. Upon stumbling on this geographical wonder I said to myself, “Wow, wouldn’t it be great to visit both within a single 24-hour period?!!!” Thus was my 2016 High-Low Expedition born.

…astonishingly, America’s highest and lowest points are only 85 miles apart.

Mt Whitney Permit

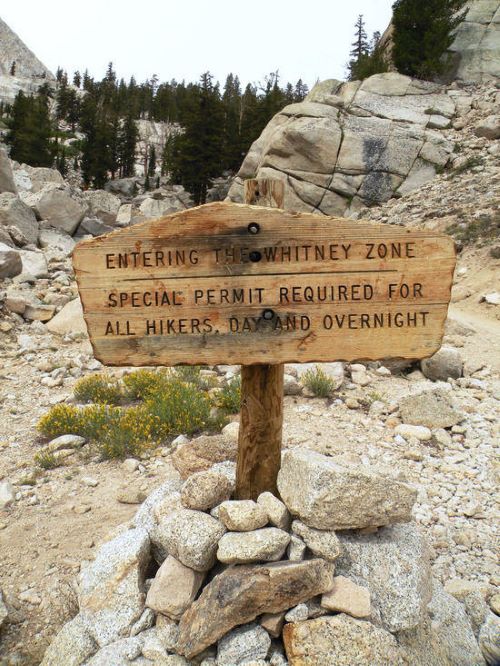

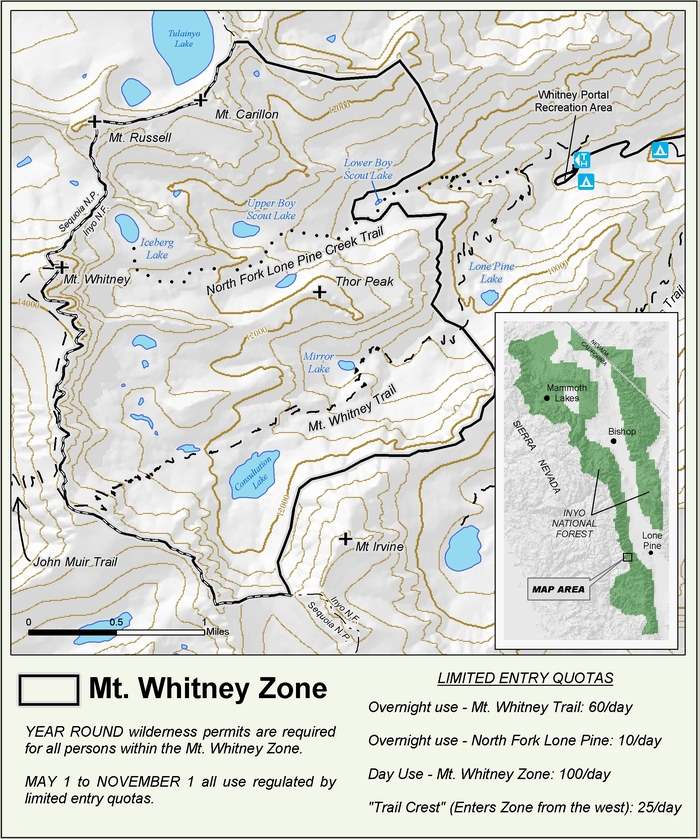

I quickly found that regulations and red tape attend any climb of Mt Whitney. The US Forest Service strictly limits the number of hikers permitted to enter the “Whitney Zone,” an area that encompasses the summit and all of the Mt Whitney Trail above 10,000 feet in elevation. Getting a permit requires planning and good luck because only 100 hikers per day are allowed into the Whitney Zone during the months of May through October. A further 60 would-be summiteers per day are allowed to camp overnight in the Zone during that period. Located as it is only 3 ½ hours by car from Los Angeles the available permits go fast and a lottery system determines who gets them. Based on data from 2015 only 43% of applicants “win” the chance to climb the mountain on their chosen dates. Full information about the lottery system is available here.

…The bigger pool of last minute permits comes from no-shows.

Hikers with flexible schedules have a second bite at the apple. Last minute cancellations of permits occasionally occur and walk-in applicants can apply for these any day of the week when the USFS Visitor Center in Lone Pine, California opens at 8am. Cancellations are fairly rare because the USFS has a no-refunds policy and most people whose plans change simply do not show up. The bigger pool of last minute permits comes from no-shows. “Day-use” permit holders are required to pick them up at the Visitor Center by 1pm on the day before their hike. Anyone who fails to meet the deadline forfeits and starting at 2pm the permit is available to anyone else who happens to be on line. “Overnight” permit holders are required to pick them up by 10am on their entry date. Forfeited overnight permits are likewise available starting at 11am to anyone present. While daily no-shows are inevitable the demand for forfeited permits can be heavy. When there are more walk-in applicants than available permits the Forest Service holds a drawing to determine who gets them. It is entirely possible to be twice unlucky when applying for a permit to enter the Whitney Zone so walk-ins need to flexible in their travel plans.

As for me, I entered the lottery in early March (it runs from February 1 through March 15) and selected May 31 and June 1 as the dates I wanted to be in the Whitney Zone. Shortly after the lottery closed on March 15 I got the good news that I had won Day-use permits for both dates. As soon as they were confirmed I reserved a tent site at the Whitney Portal Campground for the nights of May 31 and June 1. Full information and on-line booking for the Campground is available here. Only 47 sites are available and they go very quickly. Early booking is absolutely essential.

Getting There

Mt Whitney is convenient to approximately nowhere. Those flying in from distant points can choose to land in either Los Angeles or Las Vegas and from there must rent a car to travel the remaining 225 miles (from LAX) or 235 miles (from LAS). In either case the journey to Whitney Portal takes 3 ½ to 4 hours.

…Since I was planning on visiting Badwater after climbing Mt Whitney, for me travelling through Las Vegas was the only sensible choice.

I chose to fly into Las Vegas because the route to and from there takes you through the heart of Death Valley. A 17 mile diversion off the main highway brings you to Badwater Basin. Since I was planning on visiting Badwater after climbing Mt Whitney, for me travelling through Las Vegas was the only sensible choice.

Planning the Mt Whitney Climb

When planning my trip I made two critical choices.

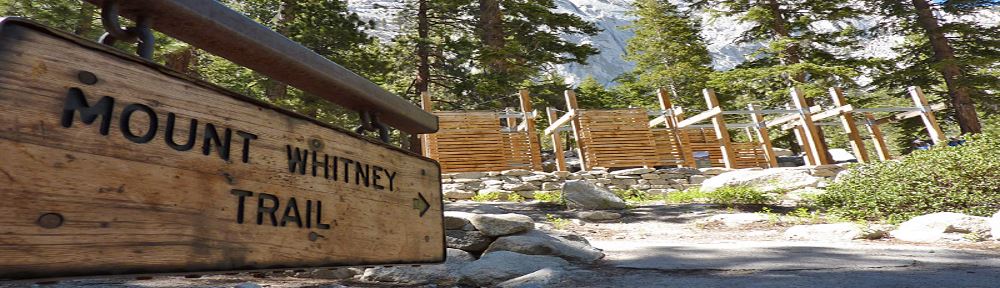

First, I decided to climb the mountain using the non-technical Mt Whitney Trail Route. I rejected the other option, the Mountaineer’s Route, because 1) route-finding on it is challenging, 2) the technical terrain (class 3) and objective dangers (rock fall, etc.) make it better suited for a group than a solo climber like me, and 3) I wanted to enjoy the ascent rather than fretting about falling off the mountain. In contrast, the standard Mt Whitney Trail Route is nothing more than a long (11 miles to the summit) and strenuous (6,155 feet of elevation gain) hike to the top.

Second, I decided to do the climb as a day-hike rather than a two day affair. I agonized only briefly about this decision. While the thought of camping overnight at Trail Camp (6 miles from the trailhead at 12,000 feet of elevation) and completing the ascent the next day was attractive, I thought that it would be more rewarding to knock the mountain off in a single 22 mile push. I am afraid that I am a bit of a snob. My internal dialog was along the lines of “real men climb the mountain…they don’t take a nap at the halfway point!” Somehow it seemed to me that overnighting at Trail Camp would be cheating. Yes, I recognize that this is completely crazy. Mt Whitney is justifiably famous for shattering the legs and thwarting the ambitions of legions of overconfident climbers.

Ancillary to my decisions on route and itinerary was the question of how to acclimatize for the climb. I live in Houston at 65 feet above sea level. There are no significant hills within 100 miles of Houston. Whenever I go to high places all my acclimatization has to be done at the destination.

…I knew that just one night at elevation (8,060 feet) before tackling the summit was far from optimal but my schedule did not allow for more.

The plan I settled on was to drive from Las Vegas to Lone Pine, California (a small town about 13 miles from Whitney Portal), pick up my two Day-use permits at the US Forest Service Visitor Center there and then take a short acclimatization hike on the mountain. I knew that staying in Lone Pine (elevation 3,700 feet) for the night would not be very useful for acclimatization purposes but hoped that the orientation hike would at least begin the process. After one night at a motel in Lone Pine the plan was to settle in as early as possible at my reserved campsite at the Whitney Portal Campground, take a long slow hike into the Whitney Zone that day and do the summit climb the next day. I knew that just one night at elevation (8,060 feet) before tackling the summit was far from optimal but my schedule did not allow for more. I rationalized that I had been higher than 14,000 feet dozens of times and that I would somehow find a way to gut it out to the top. Rationalizations of this sort come easy when you are comfortably seated in front of a computer at home.

On the Mountain

My short orientation hike on Monday, May 30 was surprisingly difficult. My only objectives were to stretch my legs after being cooped up in a plane and car all day and discover where the trailhead and my campsite for the next day were. The weather was beautiful, sunny and in the low 70°F range. Nonetheless, from the very first step of my hike up the first 1 ½ miles of the Mount Whitney Trail memories of how brutally tough it is to perform at altitude came rushing home. I was not in Houston anymore! After gaining a bit over 700 vertical feet and tagging 9,050 feet of elevation I called it a day. Naturally, going downhill did not hurt at all.

While at the trailhead I had the opportunity to ask a just-descended hiker about conditions on the route to the top. The news was depressing: the “99 Switchbacks” portion of the route above Trail Camp was completely engulfed in snow and impassible. Virtually no one was making a bid for the summit. This confirmed the news I heard earlier in the day from a USFS ranger when picking up my permits. The ranger said that 1) there was snow on the trail above 10,000 feet making the approach to Trail Camp slower than usual, 2) anyone trying for the summit needed to be equipped with ice axe, helmet and crampons, and 3) conditions made it advisable for Day-use hikers with summit ambitions start out as close to midnight as possible. Equally cogent testimony about problems on the route came from the fact that the trailhead was virtually deserted. I was there at around 6pm and expected it to be buzzing with activity. Rather, it looked like a ghost town with dozens of empty spaces in the parking lot and only a small number of people anywhere in sight. During my acclimatization hike I met only two or three casual hikers on the trail.

Hope springs eternal. Although I had left my ice axe and crampons at home I thought that the warm weather might quickly reduce the snowpack and make the route feasible again. With luck, I thought that the 99 Switchbacks would clear off enough to allow ascent aided by the trekking poles and light snow spikes that I had brought along.

…The only real downside about the Campground was that it is fully a mile distant and 300 vertical feet below the Mt Whitney Trail Trailhead.

After a night in Lone Pine I arrived back at Whitney Portal early on May 31 and set up my tent in the Campground. The tent site was wonderful. It was level, had good drainage and the tent anchors went in without hitting any rocks. There were bear-proof food lockers, picnic tables and a water spigot nearby. A toilet was just 100 yards away. It even had a dedicated parking spot. The only real downside about the Campground was that it is fully a mile distant and 300 vertical feet below the Mt Whitney Trail Trailhead. Counting as either a benefit or detriment depending on your perspective, there was no cell phone service at the Campground or anywhere else at Whitney Portal.

After settling in at the Campground I drove up the hill to the Trailhead (elevation 8,350 feet.) Ominously, I had no trouble finding a parking space. With no hikers around to quiz about conditions I spoke to the clerk at the Whitney Portal Store. He confirmed that people were staying away in droves and business was unusually light. It did not take a genius to figure out that news about difficult conditions had spread far and wide and most folks were waiting for better days.

When planning the trip, my original intention was to do an acclimatization hike all the way to Trail Camp. But, after the previous day’s altitude-related discomfort I decided to limit the hike to 6 miles. I was worried that the acclimatization benefits of a 12 mile round trip to Trail Camp would be outweighed by the energy expenditure it would cost. I knew that I would need all the energy I could get for a possible summit attempt the next day.

…Some descending climbers said that only viable way to get to Trail Crest (13,780 feet and 2 ½ miles distant from the summit) was up the Chute.

The Whitney Trail is a pleasant place to hike and the day was generously warm. Despite the lack of traffic, the route was generally well worn in and easy to follow. I went uphill at a plodding 30 minute per mile pace and was chagrined to discover that even that snail-like effort felt hard to my un-acclimatized body. After an hour or so I met a pair of hikers heading down. We chatted for a while and they said that they had reached the summit the previous day. They said that Trail Camp was pretty much deserted and that going up the 99 Switchbacks was out of the question. The only viable way to get to Trail Crest (13,780 feet and 2 ½ miles distant from the summit) was up the Chute. The Chute is the steep mountain face that the 99 Switchbacks are intended to allow you to avoid. They confirmed that ice axe and crampons were necessary to go up it and said that its descent could be done as a careful glissade. They said that once you reached Trail Crest conditions were fine, just the normal high-altitude grind.

Well, that settled it. I knew that summiting was not in the cards for this trip. I continued hiking until my GPS told me I had hit the 3 mile mark (about 10,200 feet and a half mile or so beyond Lone Pine Camp), took a leisurely break there and then headed back down. From start to finish I was on the trail about three hours and arrived back at my tent in the early afternoon. I lazed around the remainder of the day in my comfortable tent. It was a great luxury to be alone in a roomy two-person tent.

Hiking to Trail Camp

My night was unusually serene. All but a scattered handful of campsites at the Campground were empty and all the party animals had apparently decided to stay home. Based on the fact that I had already decided that my hike for June 1 would be limited to the 12 mile round trip to Trail Camp I got a relaxed start and did not begin hiking until 6:30am. Just like the day before, parking was not a problem at the trailhead.

Having one overnight under my belt was helpful from an acclimatization viewpoint. However, it was not nearly enough to make the trek up the hill anything remotely resembling comfortable. After passing my high point of the previous day the increasing altitude silently pestered me with the feeling that I had grown a hundred pounds heavier and taken up smoking besides. It took me almost four hours to reach Trail Camp. I had the trail all to myself for the first two hours before encountering a pair of descending hikers who had stayed overnight at Trail Camp. They reported that the last mile of the trail before Trail Camp was covered in snow and their report proved to be 100% accurate. The route simply disappeared and was replaced with a confusing multitude of possibilities. Tracks in the snow cover went in a million different directions. It was frustratingly difficult to choose which to follow and, without the benefit of having been to Mt Whitney before, all looked equally plausible.

After some amount of chasing down blind alleys I finally arrived at Trail Camp. It took me nearly four hours to do the 6 miles and 3,650 vertical feet. This was at least an hour slower than I ever imagined possible. I rejoiced about the fact that I did not have to go any further. I was pretty well beat.

…I could have saved myself a lot of angst by paying more attention to navigation on the way in.

The trek back down the mountain began like a bad dream. I followed what I thought were my tracks but after a quarter mile saw them descending down a steep chute. I had to backtrack and eventually mounted a rock buttress that seemed to be headed generally where I wanted to go. The buttress brought me well above but parallel to a thoroughly iced-up Consultation Lake and from it I could see the snowy trail where I wanted to be. Unfortunately, I could not find a ramp to gain the snow and did not want to risk a treacherous 20 foot down-climb on steep rock. It was incredibly frustrating to be tired, on unfamiliar ground and essentially all alone (I saw only two other people at Trail Camp) at a place where route finding problems are normally nonexistent. After some tense minutes of additional probing I finally was able to work my way off the rocks onto the snow. An hour after leaving Trail Camp (to my immense relief!) I was back on the proper trail. Once home I looked at my GPS track and saw that I was never more than 100 yards off the correct route. I could have saved myself a lot of angst by paying more attention to navigation on the way in.

I arrived back at the trailhead a bit more than seven hours after starting. The trek to Trail Camp was much more difficult than expected and it was rewarding to be done with it. With my Whitney Zone permit now used and my stay at the Campground ending the next morning it was good to look forward to the second objective of the trip, Badwater Basin and the lowest point in North America.

Badwater Basin

After another comfortable night at Whitney Portal I broke camp early and was on the road to Death Valley by 6:30am on June 2. The drive covered 134 miles and took 2 ½ hours to complete.

Death Valley is aptly named. It is a place of arid desolation so inimical to life that it was sobering just to drive through it. My little rental car was hard-pressed to cope with the road’s many twists, loops, sharp uphill stretches and equally sharp descents. It was blisteringly hot outside and the possibility of mechanical breakdown in these remote environs was distinctly unsettling. I was very relieved when I finally arrived at the roadside parking lot that marked the Badwater Basin site. It was cheering to note that a dozen or so people were already there.

…Death Valley is aptly named.

The US National Park Service is the custodian/caretaker of Death Valley and it has done a very nice job in presenting Badwater Basin to visitors. Although not manned by Park Service Rangers, there are plenty of thoughtfully composed and illustrated markers which tell the story of the location. A wooden boardwalk allows visitors to walk some distance out onto the broad salt flats and folks who so desire can march as far out onto the flats as common sense and resistance to heat will take them. A sign near the end of the boardwalk reads “Badwater Basin 282 feet below sea level.”

The sign lies!

The sign is really at 280 feet below sea level and to get to the true North American low point of minus 282 feet you have to keep going for another 3 ½ miles. Here is the GPS point to navigate to:

N 36° 14.512’

W 116° 49.529’

I had loaded the cleverly named “Lowest Point US” waypoint in my GPS before leaving home so it was just a matter of selecting it, hitting the “GO” button and following the pointer arrow. My fondest hope was that I would be able to find the famous “-282” rock that someone had carried out onto the flats years ago.

Hiking away from the populated precincts of the Badwater visitors’ area felt like jumping into the deep end of a very dry pool. It was already ferociously hot (112° as I later learned) and the sun beat down from a cloudless sky. The mosaic of salt pans shimmered in the awful heat and looked singularly evil. An honest-to-goodness life-threatening devil’s playground! I had second thoughts about going off all alone into the wasteland but suppressed them and got on with the hike. I carried two liters of water in my backpack. Happily, navigation was a breeze. The salt flats at Badwater Basin are hemmed in by mountains running north and south on both sides. The route toward the low point ran west-northwest and the entire width of the flats between the mountains was only about 8 miles. With 10,000 foot mountains directly in my line of travel it was easy to pick out landmarks to walk towards. After hiking 50 minutes I looked at my GPS for the first time since starting and saw that I was only a quarter mile from my destination. Upon making a small course correction I immediately saw a small cairn of rocks in the distance. Eureka!

…Ten steps from the cairn my GPS said “beep” confirming once again the miraculous accuracy of satellite navigation.

Ten steps from the cairn my GPS said “beep” confirming once again the miraculous accuracy of satellite navigation. To my great joy the cairn contained the “-282” rock. It was faded and sun-scorched but indisputably the one I was hoping to see. My heartfelt thanks go out to whoever it was that lugged it and all those other rocks out into the middle of the basin!

I took a couple of photos, drank a liter of now-very-warm water and made tracks for the visitors’ area. Reflections off car windshields made travelling in a direct line toward it dead easy. Less than two hours after first starting off I was back in my car. I was absolutely thrilled to be successfully done with the “low” leg of my high-low expedition. Another 2 ½ hours of driving and 140 miles brought me to Las Vegas. Along the way I stopped off at a 7-Eleven and got the Slurpee that I had fantasized about while in the desert. It immediately gave me brain-freeze.

There’s Always Next Year

The good thing about failing to reach an objective is that it gives you the opportunity to learn from your mistakes. I made three major blunders in my attempt to climb Mt Whitney.

First, I had a woefully inadequate acclimatization plan. Two short acclimatization hikes and one overnight at Whitney Portal Campground were not enough to make a summit attempt sensible or feasible. Next time I will plan on spending a minimum three nights at altitude before doing the climb. The Onion Valley Campground is only 40 miles by car from Whitney Portal and is at an elevation of 9,200 feet. From it reasonable day hikes can get you to 12,000 feet. It seems like a great place to get the body accustomed to the demands of altitude. While reservations are required, permits are not and the demand for campsites is likely to be somewhat less intense than that at Whitney Portal. More information about Onion Valley Campground is available here.

Second, I did not heed the warnings that the Forest Service makes in its online description of the Mt Whitney Trail that the route is generally not clear of snow until the end of June. Picking June 1 and hoping for the best was unwise. Next time I will try to get a permit (an Overnight permit!) for a date later in the season.

Third, it was silly to leave home without ice axe and crampons. Even if I had acclimatized well enough to take on a technical ascent I would have been stymied by my failure to bring them along. Next time I will bring my full mountaineering kit just in case!

Final Thought

Climbing and hiking these days in federally administered zones is fraught with deliberately planned bureaucratic inconveniences. On a mountain as gigantic as Mt Whitney who was it who decided that anything in excess of 160 hikers per day was too much? Will the mountain collapse under the weight of one, two or five hundred more?

…I have to admit that it is more than worth the troubles once you get to the mountain.

As galling as it is to have to jump over the roadblocks, to patiently apply for a permit in the time window allowed, to hope for a good result in the permit lottery, to accept that spontaneity is out the window and your trip has to be planned like a military campaign, I have to admit that it is more than worth the troubles once you get to the mountain. Personally, I can’t wait to get back there and give it another go.