Greenland Crossing Failure

Expedition Report: 2014 Greenland Crossing

Introduction

In April of 2014 I attempted a ski crossing of Greenland. The trip ended unsuccessfully when I left the expedition far short of the goal. Nonetheless, it was a unique experience. While I keenly regret failing to reach the finishing line, I do not regret having tried.

….before the expedition began, I thought I had done my homework.

The forensics of my disappointing failure are simple: too much weight in the sledge, too little strength to cope with it, a terribly bad choice in hand protection, appalling weather on the good days and life-threatening weather on the bad ones.

Before the expedition began, I thought that I had done my homework. Having sledged to both the North and South Poles I was confident about being able to cope with the cold and man-haul a heavy load across 335 miles of ice. I made a special effort to hone my cross country skiing skills by doing many training miles earlier in the year. It never once occurred to me that I would fail. Belief meets reality!

Starting Out

Sometimes the universe seems to be sending you a message.

After packing the car with skis, boots, duffel bag and all the gear necessary for a month-long crossing of Greenland I was eager to get to the airport and start the adventure. My wife turned the key in the ignition and…nothing. We borrowed a neighbor’s car for the drive to the airport.

…Lost luggage…another omen to ignore!

Eighteen hours and two plane changes later I finally arrived at Reykjavik, Iceland, the assembly point for the expedition. After passing through immigrations I went to baggage claim to collect my gear and…nothing. Icelandair seemed genuinely puzzled about where the bags might be. They promised to track them down and assured that lost luggage was usually recovered within “a few days.” This was not a little alarming since I was scheduled to fly to Greenland at noon just two days later.

In the event, the bags were located the next morning in some faraway corner of Newark Airport and were shipped out on the evening flight to Reykjavik. They were in my grateful hands in another day. This was a huge relief and convinced me that I would have nothing but smooth sailing for the rest of the trip. After all, what else could go wrong?

Not many days later I found out.

Expedition Staging In Greenland

The flight from Reykjavik to Kulusuk, Greenland takes only two hours. Because Greenland time is two hours behind Iceland time the plane arrived at exactly the same hour as it took off. Air Iceland runs two flights per week to Kulusuk, an island about thirty miles from the mainland. For those keeping score let me note that Air Iceland is a completely different airline from Icelandair. In a world of unlimited branding opportunities it is a mystery why these two chose to call themselves essentially the same thing. This is particularly so because Icelandair embraces the no-frills / minimal-service approach while Air Iceland positively knocks itself out to provide a pleasant passenger experience.

…everybody who comes to Greenland seems to be in admirably good shape.

I was part of a five person expedition team outfitted and guided by Reykjavik-based Icelandic Mountain Guides (“IMG”). For us, Kulusuk was just a transit point along the way to Tasiilaq, a town on another island fifteen miles closer to the mainland coast. While waiting in the small but very crowded Kulusuk terminal for our helicopter shuttle to Tasiilaq two things were readily apparent. First, everybody who comes to Greenland seems to be in admirably good shape. Men and women, young and old, all were lean and fit looking. Virtually everyone was dressed in the latest in top quality technical clothing and wearing it with the easy familiarity that comes with active use. What a contrast to the collection of harried, out-of-shape business types and casual travelers one sees in airports everywhere else! Second, it was more than clear that Air Greenland, which runs the helicopter shuttle to Tasiilaq and the vast bulk of the domestic air traffic in Greenland was untroubled by the thought of disappointing customers who entertained hopes that their flights would proceed according to schedule. It seemed that for Air Greenland schedules were mere indicators of possibilities rather than promises of service.

After a couple of hours of Olympian indifference Air Greenland allowed that it was ready to carry us to our destination. We hopped aboard the Bell 212 helicopter (an updated variant of the Viet Nam era “Huey”) and fifteen minutes later were at Tasiilaq, the “capital of East Greenland.” Not long after we were comfortably installed in a tidy 3-bedroom guesthouse that we had all to ourselves.

Tasiilaq is an interesting place. It is by far the biggest community on Greenland’s sparsely inhabited east coast. The population is about two thousand (sixth largest in all of Greenland) and it boasts two hotels, a hospital, church, grocery store and a pizzeria. It even has a small downhill ski area that is serviced by a rope-tow. There are dozens of snug looking cottages clustered on the hillside above the town’s well protected harbor as well as a number of two-story row houses. One cannot describe the town as prosperous-looking but it certainly gives the impression of purposefulness. It is ringed by an icebound sea and rugged mountains. On a coastline that supports little life and demands much of its population, Tasiilaq is a beacon of warmth and security. The contrast between the safety within and hardships of life just beyond the town limits takes little effort to appreciate.

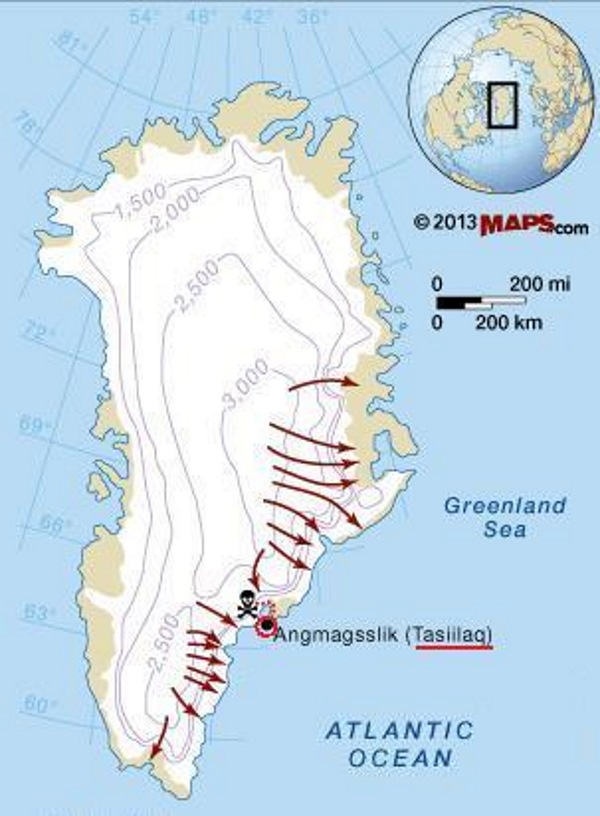

…Tasiilaq was completely destroyed in 1970 by a fierce arctic storm called a “piteraq.”

According to a short guidebook at the guesthouse, until 1993 Tasiilaq was known as “Angmassalik.” Many maps still show it as Angmassalik and others list both names. No explanation was offered for why the name was changed. Throughout Greenland place names have been changing in recent decades to substitute traditional Greenlandic names for the ones chosen by Danish colonials. Thus, for example, Godthab became Nuuk and Sondre Stromfjord became Kangerlussuaq. The renaming of Tasiilaq was curious because one Greenlandic name was swapped for another. The guidebook noted that the local business community was relieved that the change did not deter tourists who seemed to be able to find it equally well under either name. In a foreshadowing the significance of which I did not appreciate at the time, the guidebook also mentioned that the town was completely destroyed in 1970 by a fierce arctic storm called a “piteraq.”

We spent two nights in Tasiilaq, a bit longer than planned because Air Greenland decided to give the helicopter pilot a vacation day on the day we were scheduled to be dropped off on the icecap. We used the extra time to consolidate our food, fuel and gear and apportion it into equal sledge loads.

On the Icecap

Prior to loading our sledges onto the helicopter we weighed them. Mine was at the lower end of the average at 170 pounds, pretty much exactly what I weigh. The load was composed of about 40 pounds of personal gear (sleeping bag, clothing, crampons, backpack, etc.) and 130 pounds of food and group camping gear. The food was packed in individual bags labeled Day #1, #2, #3 and so on. The food bags were distributed among us so that consumption would reduce everyone’s load at a relatively equal rate. The idea was that you would grab a food bag in the morning and it would provide the day’s ration for everyone in the group. This was an eminently reasonable system that only demanded that the expedition members keep track of the bag numbers in their control. Simple is always good in stressful situations.

The helicopter ride onto the icecap was short but absolutely spectacular. After rising over the mountains encircling Tasiilaq we got our first view of the mainland. Coastal Greenland is like a huge elongated cup with 4,000 foot high mountains forming a narrow rim that confines the inland ice. Once you make the leap over the mountains you see nothing but ice stretching limitlessly to the horizon. The inland ice is a giant frozen lake whose shores are defined by the mountains. Like any glacier, it is always and inexorably on the move and seeking an outlet at the sea. From the helicopter we could see areas where it breached the coastal range and funneled its way to the ocean.

We were dropped off just beyond the inside edge of the mountains at an altitude of about 3,600 feet. In a helicopter ride of about ten minutes we were transported from a world of men and machines to an icy primordial vastness where our presence amounted to nothing. There are times when you sense your smallness and this was one of them. The ice and mountains had been there for millenniums and bore not the slightest trace of human presence. I think each of us felt humbled to be on such a grandly indifferent stage.

…Per my GPS, our first and only waypoint on the route to the west coast, the long-abandoned DYE-2 radar station, was 221 miles away.

Of course, I was also elated to be there. After months of planning and preparation, the adventure I had mentally rehearsed a thousand times had actually started. It was wonderfully comforting to go through the familiar rituals of donning skis, attaching sledge traces and adjusting poles. Within fifteen minutes of landing our group of five was underway. Per my GPS, our first and only waypoint on the route to the west coast, the long-abandoned DYE-2 radar station, was 221 miles away. The distance did not faze me in the least, nor did the fact that the first three weeks of the journey would be uphill, rising to the summit of the icecap at 8,200 feet.

It was instantly apparent that conditions on the inland ice would be dramatically different from those we enjoyed in Tasiilaq. There, daytime temperatures were as high as 45°F and lows not much below 20°F. When we landed on the ice it was 3°F and as we progressed through the afternoon it got considerably colder.

Since we did not reach the icecap until 1 pm, our first day of sledging was a short one. We did two ninety minute skiing stages separated by a twenty minute rest break. Despite the easy schedule, from the very beginning my sledge felt monstrously heavy and I was shocked by the amount of effort it took to haul it over obstacles. It was very strange because the ice conditions looked perfectly benign. In my last sledging experience two years before over the chaotically fissured and up-thrust sea ice in the vicinity of the North Pole conditions were infinitely more challenging. There, ten foot high pressure ridges had to be surmounted on a regular basis. In Greenland all we had to deal with were legions of three to six inch ridges of wind-sculpted ice. These ridges, known as “sastrugi,” ran like corduroy across our westward line of march and formed a barrier of mini-obstacles that looked innocuous but were confounding in their ability to impede progress. Of course, the sastrugi were only part of the problem. The bigger issues were the weight of the sledge and our uphill trajectory.

My 170 pound sledge would have been a huge burden to drag along in the best of conditions. Very cold ice is not at all slippery. The surface we were pulling over felt more like sand than ice. While my skis gripped the ice well I found every step difficult. This came as a huge surprise since at the North Pole I was able to handle a 100 pound load without any concern. I had always assumed that the heavier sledge would be incrementally tougher to pull. What I found was that it was geometrically harder.

As a veteran mountaineer I am more than familiar with the difficulties of going uphill. However, it never occurred to me that the modest 4,600 foot elevation gain we would make in ascending to the summit of the icecap would be challenging. In fact, it was extremely challenging, all the more so because the ascent was so gentle that my eyes told me that I was not going uphill at all. Appearances are deceiving. While my eyes classified the slope as trivial, my legs violently disagreed with that assessment. In our first day of travel we gained over five hundred feet of altitude. Every inch of it was hard-won.

…I was very happy to be able to call it a day and start building camp. That is when the real work started.

By the time we reached our stopping point for the day I was impressed with how big an undertaking crossing the inland ice would be. While I felt well, I was very happy to be able to call it a day and start building camp. That is when the real work started.

The first few days of any expedition are always awkward when it comes to making and breaking camp and this one was no different. Our two five-pole mountaineering tents were well chosen for their strength and durability but had all the complexity of a Rubik’s Cube in our unpracticed hands. Inevitably you find that the last guy who used the tent packed it without the slightest regard for who would use it next. We had the usual catalogue of complaints: loops undone, knots in the stays, Velcro fasteners gummed up, poles that refused to seat in their sockets, etc., etc. Our frustrations were perfectly typical. However, in the two hours it took to get the tents erected I made an error that cost me dearly. I took off my gloves to do some of the fiddly work and in so doing froze the tips of several fingers. I should have known better. There is no question that frostbite has a memory. It attacks first in the places where it has previously gained purchase and years of expeditions in cold places have left my fingertips particularly susceptible. Thus, on Day One of a month long expedition I planted the seeds for potentially serious trouble. By the time we got the tents up the temperature had dropped to minus 3°F.

Because the wind was only moderately gusty, we ate dinner before building a wall to protect our campsite. Dinner provided a nice respite and when we emerged from the tents to tackle the wall I felt good. Based on a favorable weather report we judged that the wall could be fairly simple. It took us about an hour and a half to create a five foot high semi-circle with a diameter large enough to deflect the prevailing wind away from the tents. By 9:00 pm we were tucked away for the night in the tents.

Weather on the Icecap

Upon waking up the next day, it was immediately apparent that the weather had taken a turn for the worse. I went out at around 6 am for a bathroom break and was dismayed by the strength of the wind. After a quiet night, the wind had begun buffeting the tents a couple of hours before. Its strength was such that it blew the toilet paper roll from my half-frozen hands and I saw the roll tumbling away at thirty miles per hour unwinding like a ribbon from a spool. It would have been funny except for the fact that it was by then down to minus 5°F and I needed that toilet paper.

By 8 am the wind had abated to a more reasonable twenty miles per hour and we began breaking camp. It took us three very cold hours to do so. We were careful to pack the tents meticulously so as to minimize frustration upon re-erecting them in the evening. We were mindful that we would no longer have the negligent and anonymous “last guy who used the tents” as a target for our wrath and fervently wanted the next tent building drill to go smoothly.

We began skiing at around 11 am into a strong quartering wind out of the northwest. We all wore goggles and balaclavas to protect our faces. Progress was slow due to the resisting effect of the wind. However, a more immediate concern to me was that my hands were freezing. As the day wore on it became increasingly apparent that my hand protection scheme was not working as intended. The chief problem was that I relied on a pair on ski pole-mounted “Bar-Mitts” to keep my hands warm. The Bar-Mitts were insulated neoprene sacks, open at one end for the hands and with a hole at the bottom to squeeze the grips of the ski pole through. The idea was to create a snug, windproof environment for the hands that was mitten-like in warmth but allowed the use of simple liner-gloves inside of them. In theory you would have the warmth of mittens and the dexterity of gloves in one integrated system. In theory.

In practice, I had a good windbreak but very little warmth. All the warmth came from the gloves and in cold conditions that was not nearly enough. I was persuaded to try the Bar-Mitts because the design looked attractive and I had used roughly similar contrivances (called “pogies”) with great success on a trip to the South Pole a few years before. The pogies were made to order for the Antarctica trip operator and were not available at retail. I chose the Bar-Mitts as the best (and only) alternative to pogies and made the critical mistake of assuming they would work without verifying their effectiveness in the field. Big mistake!

As a result, my hands were frozen and numb for the first half hour of every sledging stage. While the effort of skiing eventually would generate enough body heat to reach my fingertips, the heat dissipated quickly during rest breaks. The pattern of freeze-warm, freeze-warm, freeze-warm had very bad consequences.

…For most of the day, conditions were oppressively difficult with the steady, if invisible, uphill grind, heavy sledges, limitless sastrugi, sub-zero cold and unremitting wind.

Meanwhile, we were still going uphill and by the end of the day gained roughly another five hundred feet of altitude. In the last couple of hours of the day it got much, much worse and we came to learn firsthand what a “piteraq” is.

The Greenland icecap is known for its katabatic winds. They are creatures of an icebound topography that features a dome of ice radiating from the middle of the island and gradually thinning as it approaches the coast. The summit of the icecap is 8,200 feet above the sea and because air loses its ability to retain heat as altitude increases it gets progressively colder the further up you go. Cold air is also denser than warmer air and it is natural for very cold, dense air to pool at the higher areas of the inland ice. Eventually, that pool of cold, dense air literally begins to fall downhill towards the coast. As it goes it gains momentum and the falling air creates a powerful wind: a “katabatic” wind. We were no strangers to the “normal” katabatic flow of air. Ever since landing on the icecap we had been exposed to a northwest wind that fluctuated in strength between a gentle ten mile per hour breeze and the buffeting thirty mile per hour gale of the early morning.

A piteraq (pronounced “peter-rack”) is a special kind of katabatic wind. It is different from a normal katabatic in that the downhill flow of air is intensified by an offshore low pressure system in the Greenland Sea. Instead of simply falling towards the coast, the intensely cold, heavy air on the summit is actively sucked toward the coast by the offshore low. In other words, the fall turns into an avalanche. Just as a snow avalanche seeks the line of least resistance by funneling into natural couloirs, so too the piteraq canalizes into a relatively narrow chute formed by the inside edge of the mountains in the east and the ever-rising icecap in the west. We had the bad luck of being in the middle of the chute when the piteraq hit.

After struggling against the increasing wind throughout the last ninety minute stage of the day we finally stopped and began to build camp. It took us almost four hours to get the tents up and sturdy walls built. The work was horrific. Anyone who has erected a tent in a strong wind understands what a struggle it is to deal with violently flapping nylon and straps that refuse to sit still long enough for you to tighten them. We had the added burden of minus 5°F cold that felt like minus 35°F due to the wind chill. The tent building took about two hours and building the walls a further two hours. The wall building exercise was difficult but absolutely essential. Without walls to protect them the tents would not have lasted through the night. We used saws to cut hundreds of snow blocks out of the ice and stacked them to create a sturdy rampart on the windward side of the tents. By the time we were done it was after 9 pm and I was on the verge of hypothermia. I got in my sleeping bag and shivered violently for the next hour. The piteraq had done its work.

Dinner provided welcome relief and restored warmth to all of us. Morning and evening, “cooking” consisted of boiling water over the primus stove and transferring it to thermos bottles. Each of us had a one-liter thermos and used it for making hot cocoa or tea, hydrating our dinnertime packet of freeze-dried stew and preparing the morning bowl of cereal. It was a great luxury to pour the hot water into the foil freeze-dry packet and let the heat radiate into the hands. However, I had already learned that on this expedition fuel was too precious to waste on heat for the tent or de-icing frozen clothes. All the water boiling was done in a snow pit in the vestibule of the tent. Regrettably, almost no heat at all escaped into the tent. The warmest the tent ever got with all five of us inside for dinner or breakfast was 33°F. With no waste heat to dry our iced-up facemasks and gloves our gear simply stayed iced-up. While drying would have been possible by bringing the stuff into the sleeping bags, none of us wanted to risk compromising the bags with too much moisture. Donning hard-frozen facemasks every morning was a wretched experience.

After dinner I took stock of my situation. I looked at the frostbite blisters that had formed on my fingertips and fretted about the likelihood that further exposure would inflict real damage to them. I considered the terrible effort it took for me to drag my heavy sledge. Most of all, I reflected that we were less than a quarter of the way to the summit of the icecap and that another two weeks and 3,600 feet of climbing remained before we would begin the descent to the west coast. While I knew that my sledge would gradually lighten as we consumed our food, a decrease of just ten pounds every fourth day did not seem nearly fast enough to do me much good. I reluctantly concluded that I simply was not strong enough to complete the crossing. Moreover, in light of the desperate struggle we had in building camp in the midst of the piteraq, I weighed our safety margin and found it uncomfortably slim.

…It was difficult to admit defeat but the facts were undeniable.

It was difficult to admit defeat but the facts were undeniable. After a night’s reflection I asked the guide to organize a helicopter flight off the icecap. The request was discussed with IMG in Reykjavik over the satellite phone and IMG liaised with Air Greenland. After some discussion, Air Greenland promised to send a helicopter to our campsite at 4 pm. By mid-morning the piteraq had blown itself out and the temperature was up to 3°F. We could have used the day as a travelling day and had the helicopter meet us en route but, conscious of the very hard pull we had the day earlier, we took a rest day during which we went through all of our food and equipment and decided what to keep and what to send back with me. We repacked all the food bags and sledges and mine lost about forty pounds in the process. By 2 pm the repacking was done and nothing was left but to await the ride back to civilization.

The helicopter never came.

More satellite phone calls to Reykjavik ensued and IMG did its best to discover what had gone wrong. They had no luck at all because nobody was answering the phone at Air Greenland’s headquarters in Nuuk. IMG’s contact person in Tasiilaq went down to the heliport and found the helicopter safely tucked away in its hangar. He happened on a group of three disappointed travelers outside the terminal forlornly wondering why nobody from Air Greenland was there to take them on their scheduled flight to Kulusuk.

Piteraq’s Big Brother

While IMG could not explain why Air Greenland dropped the ball, they had other infinitely more important information to share with us: the latest weather report. The substance of the report was that a giant storm was headed our way. They advised us to begin fortifying our campsite because we would likely be pinned down by the storm for a few days.

The next morning we woke to a whiteout and uncharacteristically warm conditions. After days of temperatures no higher than 5°F, the sudden change to 20°F felt positively tropical. After breakfast we began reinforcing our main wall and building an entirely new one for the second tent. We spent about six hours on this work. In the process we sawed, shoveled out and stacked hundreds upon hundreds of snow blocks. It was exhausting work but in the end we had gigantic, four-foot thick walls that looked sturdy enough to resist anything.

By mid-afternoon, the whiteout dissipated and you could glimpse the tops of the coastal mountains many miles away. IMG reported that Air Greenland still was not picking up the phone so there would be no evacuation in the lull before the storm. They said that the Danish Meteorological Service had issued a piteraq warning to the coastal communities in the Tasiilaq area. They emphasized that the storm would be very powerful.

…By midnight the tent was being buffeted with such violence that it seemed unlikely to survive the night.

At 8 pm the temperature abruptly plummeted to 0°F and the wind began to howl. By midnight the tent was being buffeted with such violence that it seemed unlikely to survive the night. I have never been in a storm nearly so awful. The din made communication impossible and all of us felt utterly helpless. Throughout the night we huddled in our sleeping bags fully dressed against the possibility that one or both tents would be torn to pieces. Before the piteraq hit I considered that our six-hour wall building marathon was an exercise in overkill. Now I cursed the fact that we had not put double the amount of time into the job.

At midmorning the next day the piteraq was still blowing with unabated violence and drifting snow had partially engulfed the tent. We decided to go outside and try to relieve the tent of the weight of the snow. We also wanted to inspect the walls to see whether they required work.

After ten minutes outside in the arctic hurricane it became apparent that the mission was an exercise in futility. It was literally impossible to stand upright in the gale. Goggles became opaque with wind-driven snow in seconds. Even with your back to the wind, vision was thoroughly obscured by the drift racing by at eighty miles per hour. The wind was an all-consuming, irresistible physical presence that threatened to tear you off your feet and send you tumbling into oblivion. The piteraq was so utterly outside any notion of “bad weather” that I had ever imagined that it was almost entertaining to be a firsthand witness to it. It occurred to me that most people who see a storm like this while in the field are probably killed in the process. With that sobering thought, I struggled back into the vestibule of the tent. It was like entering paradise. While the tent was still snapping and buffeting wildly, the giant’s hands had let go of my body and I could once again look around without being blinded. It was odd to feel so much infinitely safer than I did outside. I did not tarry over the thought that my security was entirely reliant on a few stitched-together pieces of gossamer-thin ripstop nylon.

While collecting myself in the vestibule I noticed that I had grown unaccountably fat around the waist. It was because I had not closed the pocket zippers of my big down parka before going outside. In my ten minutes outdoors the pockets had filled to the bursting point with snow. Useful lesson learned: zip up your pockets before going out into a piteraq!

The piteraq finally blew itself out around midnight, about twenty-eight hours after starting. It was odd to wake up in the middle of the night and hear silence.

…Everyone agreed that the piteraq was the worst storm they had ever witnessed.

At breakfast we all gathered together for our first group meal in two days. Everyone agreed that the piteraq was the worst storm they had ever witnessed. No one could remember any other storm that was even in the same league. We agreed that “Baby Piteraq” who we met a few days before was an insignificant nobody compared to his massively violent, steroid-popping sibling, “Big Brother Piteraq.”

A couple of rounds of calls on the satellite phone confirmed that Air Greenland would send a helicopter to our camp that morning. This was cheering news until IMG called minutes later to say that Air Greenland had changed its mind and would not be able to come until after it had made some of its scheduled runs to the local communities and had done “routine maintenance” on the machine. Air Greenland did not even venture a guess as to when this might be.

Continuing On

Naturally, with no helicopters on the horizon and favorable weather we were anxious to push forward on the route. However, digging out after the storm was a time-consuming business. The tents were half buried and the sledges were barely visible. It took three hours to break camp and get underway. While the temperature was back down to minus 3°F, mercifully the wind was unusually gentle.

Although my damaged hands were still freezing under three layers of gloves and the Bar-Mitts, I was astonished to find the sledging very easy. My newfound feeling of strength was due to two factors: 1) in repacking, my sledge had lost forty pounds of weight, and 2) the vertical ascent for the day was a very modest 170 feet. It was wonderful to ski with such a degree of physical comfort. The sastrugi continued to cause the sledge to heave and bump but I had no trouble pulling it over the endless ridges. It struck me forcibly that the margin that separated me from success on this expedition was a miserable forty pounds.

However, I did not reconsider my decision to leave. Bumping up against my physical limitations was a disheartening experience and I no longer had the enthusiasm needed to continue sledging for another three weeks. I wanted to get out and the sooner the better. I had already begun to fantasize about a hot shower, comfortable bed and effortless warmth. It was tantalizing to think that all those things were only a thirty minute helicopter ride away. At our lunch break, IMG called with good news about my evacuation. They had given up on Air Greenland and instead had found a heli-ski operator who was scheduled to arrive at Kulusuk later that day. The heli-ski guy said he was willing to send his machine to come and get me. Weather permitting they said that I would be picked up the next morning. I would have been elated but for the fact that repeated disappointments made me wary about trusting anyone’s promise to get me off the ice.

We put in a full day on the route and had the tents up within an hour and a half. With no storms on the horizon we were able to build a relatively simple wall. The temperature had dropped to minus 8°F but it did not feel at all bad because of the lightness of the wind. Within two and a half hours of stopping we were enjoying dinner. I thought it interesting that a twelve hour day actually felt reasonable. The Greenland crossing demands a lot from anyone who tries it.

Leaving the Inland Ice

It got very cold overnight and when I awoke at 6 am I saw that it was minus 17°F. I took this as a good sign because cold temperatures are usually associated with cloudless skies. A peek outside confirmed that the day was perfect. It was Easter Sunday.

Shortly after breakfast we heard the thump of rotor blades and all went outside to see the helicopter settle on the ice. After days of frustration and delay the arrival of the helicopter was curiously anticlimactic. My sledge was put into a skid-mounted cargo container, best wishes exchanged with the team and fifteen minutes after landing the machine was airborne again and I was on my way to Kulusuk. It was a beautiful day for flying.

…It was almost overwhelming; from an icebound minus 17°F vastness to a centrally-heated 75°F tourist hotel!

Barely an hour after leaving the ice I checked into the Hotel Kulusuk. A surreal experience! I felt like I had been magically teleported to another world. It was almost overwhelming; from an icebound minus 17°F vastness to a centrally-heated 75°F tourist hotel; from a place where your only comfort was a sleeping bag and the hot water in your thermos to a cozy room with indoor plumbing and satellite TV. It was difficult to decide which luxury to sample first. Needless to say, I will always remember my Easter in Kulusuk with gratitude and fondness. A week later I was back in Houston.

Epilogue

All my teammates were successful in completing the Crossing of Greenland. They arrived at Hill 660 outside Kangerlussauq three weeks after I left them. A job well done under some of the most vicious conditions imaginable! My hat is off to all of them.

One day after I was plucked from the ice yet another piteraq ravaged Tasiilaq and Kulusuk. The winds were measured at seventy miles per hour at the airport. The heli-ski company’s copter was knocked out of commission by the storm. I was very lucky to have completed the charter before the storm hit. When I flew out a couple of days later the helicopter was still inoperable and the prognosis for repair uncertain.

The frostbite on my fingertips took several weeks to heal. Layer upon layer of skin hardened and shed, a transition during which the fingertips progressed from being totally devoid of sensation to hyper-sensitive. Thankfully, there was no permanent damage done.

The psychological scars from the trip have largely faded as well. It was awful to be defeated by the icecap and to come to grips with the fact that my physical capacity is not as robust as I imagined it to be. Before the trip I never for a moment doubted my ability to complete it. I think that I overestimated my own strength and underestimated the difficulty of the journey. The little bit of solace that I have is that I was not too far wrong. I am sure that I could have done the trip if my sledge was forty pounds lighter. Of course, I am well aware that this is a bit like saying that I could run a marathon if only it were a few pesky miles shorter than 26.2. In the real world you have to take challenges for what they are rather than what you would like them to be. Still, it is comforting to think that the margin of defeat was trivially thin.

I am now thinking about where the next adventure will be. It is wonderful to have a world filled with exciting possibilities. Just asking the question “Where next?” is its intoxicating own reward.